|

Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta

-

Volume 3 — Only He Could Lead Them

<< 22 Swami Invites the Hippies >>

| January 16, 1967

|  | AS THE UNITED Airlines jet descended on the San Francisco Bay area, Śrīla Prabhupāda turned to his disciple Ranchor and said, “The buildings look like matchboxes. Just imagine how it looks from Kṛṣṇa’s viewpoint.”

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda was seventy-one years old, and this had been his first air trip. Ranchor, nineteen and dressed in a suit and tie, was supposed to be Śrīla Prabhupāda’s secretary. He was a new disciple but had raised some money and had asked to fly to San Francisco with Prabhupāda.

|  | During the trip Śrīla Prabhupāda had spoken little. He had been chanting: “Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare.” His right hand in his cloth bead bag, he had been fingering one bead after another as he chanted silently to himself. When the plane had first risen over New York City, he had looked out the window at the buildings growing smaller and smaller. Then the plane had entered the clouds, which to Prabhupāda had appeared like an ocean in the sky. He had been bothered by pressure blocking his ears and had mentioned it; otherwise he hadn’t said much, but had only chanted Kṛṣṇa’s names over and over. Now, as the plane began its descent, he continued to chant, his voice slightly audible – “Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa …” – and he looked out the window at the vista of thousands of matchbox houses and streets stretching in charted patterns in every direction.

|  | When the announcement for United Airlines Flight 21 from New York came over the public-address system, the group of about fifty hippies gathered closer together in anticipation. For a moment they appeared almost apprehensive, unsure of what to expect or what the Svāmī would be like.

|  | Roger Segal: We were quite an assorted lot, even for the San Francisco airport. Mukunda was wearing a Merlin the Magician robe with paisley squares all around, Sam was wearing a Moroccan sheep robe with a hood – he even smelled like a sheep – and I was wearing a sort of blue homemade Japanese samurai robe with small white dots. Long strings of beads were everywhere. Buckskins, boots, army fatigues, people wearing small, round sunglasses – the whole phantasmagoria of San Francisco at its height.

|  | Only a few people in the crowd knew Svāmīji: Mukunda and his wife, Jānakī; Ravīndra-svarūpa; Rāya Rāma – all from New York. And Allen Ginsberg was there. (A few days before, Allen had been one of the leaders of the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, where over two hundred thousand had come together – “A Gathering of the Tribes … for a joyful pow-wow and Peace Dance.”) Today Allen was on hand to greet Svāmī Bhaktivedanta, whom he had met and chanted with several months before on New York’s Lower East Side.

|  | Svāmīji would be pleased, Mukunda reminded everyone, if they were all chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa when he came through the gate. They were already familiar with the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra. They had heard about the Svāmī’s chanting in the park in New York or they had seen the article about Svāmīji and the chanting in the local underground paper, The Oracle. Earlier today they had gathered in Golden Gate Park – most of them responding to a flyer Mukunda had distributed – and had chanted there for more than an hour before coming to the airport in a caravan of cars. Now many of them – also in response to Mukunda’s flyer – stood with incense and flowers in their hands.

|  | As the disembarking passengers entered the terminal gate and walked up the ramp, they looked in amazement at the reception party of flower-bearing chanters. The chanters, however, gazed past these ordinary, tired-looking travelers, searching for that special person who was supposed to be on the plane. Suddenly, strolling toward them was the Svāmī, golden-complexioned, dressed in bright saffron robes.

|  | Prabhupāda had heard the chanting even before he had entered the terminal, and he had begun to smile. He was happy and surprised. Glancing over the faces, he recognized only a few. Yet here were fifty people receiving him and chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa without his having said a word!

|  | Mukunda: We just had a look at Svāmīji, and then we bowed down – myself, my wife, and the friends I had brought, Sam and Marjorie. And then all of the young men and women there followed suit and all bowed down to Svāmīji, just feeling very confident that it was the right and proper thing to do.

|  | The crowd of hippies had formed a line on either side of a narrow passage through which Svāmīji would walk. As he passed among his new admirers, dozens of hands stretched out to offer him flowers and incense. He smiled, collecting the offerings in his hands while Ranchor looked on. Allen Ginsberg stepped forward with a large bouquet of flowers, and Śrīla Prabhupāda graciously accepted it. Then Prabhupāda began offering the gifts back to all who reached out to receive them. He proceeded through the terminal, the crowd of young people walking beside him, chanting.

|  | At the baggage claim Śrīla Prabhupāda waited for a moment, his eyes taking in everyone around him. Lifting his open palms, he beckoned everyone to chant louder, and the group burst into renewed chanting, with Prabhupāda standing in their midst, softly clapping his hands and singing Hare Kṛṣṇa. Gracefully, he then raised his arms above his head and began to dance, stepping and swaying from side to side.

|  | To the mixed chagrin, amusement, and irresistible joy of the airport workers and passengers, the reception party stayed with Prabhupāda until he got his luggage. Then they escorted him outside into the sunlight and into a waiting car, a black 1949 Cadillac Fleetwood. Prabhupāda got into the back seat with Mukunda and Allen Ginsberg. Until the moment the car pulled away from the curb, Śrīla Prabhupāda, still smiling, continued handing flowers to all those who had come to welcome him as he brought Kṛṣṇa consciousness west.

|  | The Cadillac belonged to Harvey Cohen, who almost a year before had allowed Prabhupāda to stay in his Bowery loft. Harvey was driving, but because of his chauffeur’s hat (picked up at a Salvation Army store) and his black suit and his beard, Prabhupāda didn’t recognize him.

|  | “Where is Harvey?” Prabhupāda asked.

“He’s driving,” Mukunda said.

“Oh, is that you? I didn’t recognize you.”

Harvey smiled. “Welcome to San Francisco, Svāmīji.”

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda was happy to be in another big Western city on behalf of his spiritual master, Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, and Lord Caitanya. The further west one goes, Lord Caitanya had said, the more materialistic the people. Yet, Lord Caitanya had also said that Kṛṣṇa consciousness should spread all over the world. Prabhupāda’s Godbrothers had often wondered about Lord Caitanya’s statement that one day the name of Kṛṣṇa would be sung in every town and village. Perhaps that verse should be taken symbolically, they said; otherwise, what could it mean – Kṛṣṇa in every town? But Śrīla Prabhupāda had deep faith in that statement by Lord Caitanya and in the instruction of his spiritual master. Here he was in the far-Western city of San Francisco, and already people were chanting. They had enthusiastically received him with flowers and kīrtana. And all over the world there were other cities much like this one.

|  | The temple Mukunda and his friends had obtained was on Frederick Street in the Haight-Ashbury district. Like the temple at 26 Second Avenue in New York, it was a small storefront with a display window facing the street. A sign over the window read, SRI SRI RADHA KRISHNA TEMPLE. Mukunda and his friends had also rented a three-room apartment for Svāmīji on the third floor of the adjoining building. It was a small, bare, run-down apartment facing the street.

|  | Followed by several carloads of devotees and curious seekers, Śrīla Prabhupāda arrived at 518 Frederick Street and entered the storefront, which was decorated only by a few madras cloths on the wall. Taking his seat on a cushion, he led a kīrtana and then spoke, inviting everyone to take up Kṛṣṇa consciousness. After his lecture he left the storefront and walked next door and up the two flights of stairs to his apartment. As he entered his apartment, number 32, he was followed not only by his devotees and admirers but also by reporters from San Francisco’s main newspapers: the Chronicle and the Examiner. While some devotees cooked his lunch and Ranchor unpacked his suitcase, Svāmīji talked with the reporters, who sat on the floor, taking notes on their pads.

|  | Reporter: “Downstairs, you said you were inviting everyone to Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Does that include the Haight-Ashbury Bohemians and beatniks?”

|  | Prabhupāda: “Yes, everyone, including you or anybody else, be he or she what is called an ‘acidhead’ or a hippie or something else. But once he is accepted for training, he becomes something else from what he had been before.”

|  | Reporter: “What does one have to do to become a member of your movement?”

|  | Prabhupāda: “There are four prerequisites. I do not allow my students to keep girlfriends. I prohibit all kinds of intoxicants, including coffee, tea and cigarettes. I prohibit meat-eating. And I prohibit my students from taking part in gambling.”

|  | Reporter: “Do these shall-not commandments extend to the use of LSD, marijuana, and other narcotics?”

|  | Prabhupāda: “I consider LSD to be an intoxicant. I do not allow any one of my students to use that or any intoxicant. I train my students to rise early in the morning, to take a bath early in the day, and to attend prayer meetings three times a day. Our sect is one of austerity. It is the science of God.”

|  | Although Prabhupāda had found that reporters generally did not report his philosophy, he took the opportunity to preach Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Even if the reporters didn’t want to delve into the philosophy, his followers did. “The big mistake of modern civilization,” Śrīla Prabhupāda continued, “is to encroach upon others’ property as though it were one’s own. This creates an unnatural disturbance. God is the ultimate proprietor of everything in the universe. When people know that God is the ultimate proprietor, the best friend of all living entities, and the object of all offerings and sacrifices – then there will be peace.”

|  | The reporters asked him about his background, and he told briefly about his coming from India and beginning in New York.

|  | After the reporters left, Prabhupāda continued speaking to the young people in his room. Mukunda, who had allowed his hair and beard to grow but who wore around his neck the strand of large red beads Svāmīji had given him at initiation, introduced some of his friends and explained that they were all living together and that they wanted to help Svāmīji present Kṛṣṇa consciousness to the young people of San Francisco. Mukunda’s wife, Jānakī, asked Svāmīji about his plane ride. He said it had been pleasant except for some pressure in his ears. “The houses looked like matchboxes,” he said, and with his thumb and forefinger he indicated the size of a matchbox.

|  | He leaned back against the wall and took off the garlands he had received that day, until only a beaded necklace – a common, inexpensive item with a small bell on it – remained hanging around his neck. Prabhupāda held it, inspected the workmanship, and toyed with it. “This is special,” he said, looking up, “because it was made with devotion.” He continued to pay attention to the necklace, as if receiving it had been one of the most important events of the day.

|  | When his lunch arrived, he distributed some to everyone, and then Ranchor efficiently though tactlessly asked everyone to leave and give the Svāmī a little time to eat and rest.

|  | Outside the apartment and in the storefront below, the talk was of Svāmīji. No one had been disappointed. Everything Mukunda had been telling them about him was true. They particularly enjoyed how he had talked about seeing everything from Kṛṣṇa’s viewpoint.

|  | That night on television Svāmīji’s arrival was covered on the eleven o’clock news, and the next day it appeared in the newspapers. The Examiner’s story was on page two – “Svāmī Invites the Hippies” – along with a photo of the temple, filled with followers, and some shots of Svāmīji, who looked very grave. Prabhupāda had Mukunda read the article aloud.

|  | “The lanky ‘Master of the Faith,’ ” Mukunda read, “attired in a flowing ankle-long robe and sitting cross-legged on a big mattress – ”

|  | Svāmīji interrupted, “What is this word lanky?”

|  | Mukunda explained that it meant tall and slender. “I don’t know why they said that,” he added. “Maybe it’s because you sit so straight and tall, so they think that you are very tall.” The article went on to describe many of the airport greeters as being “of the long-haired, bearded and sandaled set.”

|  | San Francisco’s largest paper, the Chronicle, also ran an article: “Svāmī in Hippie-Land – Holy Man Opens S.F. Temple.” The article began, “A holy man from India, described by his friend and beat poet Allen Ginsberg as one of the more conservative leaders of his faith, launched a kind of evangelistic effort yesterday in the heart of San Francisco’s hippie haven.”

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda objected to being called conservative. He was indignant: “Conservative? How is that?”

|  | “In respect to sex and drugs,” Mukunda suggested.

|  | “Of course, we are conservative in that sense,” Prabhupāda said. “That simply means we are following śāstra. We cannot depart from Bhagavad-gītā. But conservative we are not. Caitanya Mahāprabhu was so strict that He would not even look on a woman, but we are accepting everyone into this movement, regardless of sex, caste, position, or whatever. Everyone is invited to come chant Hare Kṛṣṇa. This is Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s munificence, His liberality. No, we are not conservative.”

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda rose from bed and turned on the light. It was 1 A.M. Although the alarm had not sounded and no one had come to wake him, he had risen on his own. The apartment was cold and quiet. Wrapping his cādara around his shoulders, he sat quietly at his makeshift desk (a trunk filled with manuscripts) and in deep concentration chanted the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra on his beads.

|  | After an hour of chanting, Śrīla Prabhupāda turned to his writing. Although two years had passed since he had published a book (the third and final volume of the First Canto of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam), he had daily been working, sometimes on his translation and commentary of the Second Canto but mostly on Bhagavad-gītā. In the 1940s in India he had written an entire Bhagavad-gītā translation and commentary, but his only copy had mysteriously disappeared. Then in 1965, after a few months in America, he had begun again, starting with the Introduction, which he had composed in his room on Seventy-second Street in New York. Now thousands of manuscript pages filled his trunk, completing his Bhagavad-gītā. If his New York disciple Hayagrīva, formerly an English professor, could edit it, and if some of the other disciples could get it published, that would be an important achievement.

|  | But publishing books in America seemed difficult – more difficult than in India. Even though in India he had been alone, he had managed to publish three volumes in three years. Here in America he had many followers; but many followers meant increased responsibilities. And none of his followers as yet seemed seriously inclined to take up typing, editing, and dealing with American businessmen. Yet despite the dim prospects for publishing his Bhagavad-gītā, Śrīla Prabhupāda had begun translating another book, Caitanya-caritāmṛta, the principal Vaiṣṇava scripture on the life and teachings of Lord Caitanya.

|  | Putting on his reading glasses, Prabhupāda opened his books and turned on the dictating machine. He studied the Bengali and Sanskrit texts, then picked up the microphone, flicked the switch to record, flashing on a small red light, and began speaking: “While the Lord was going, chanting and dancing, …” (he spoke no more than a phrase at a time, flicking the switch, pausing, and then dictating again) “thousands of people were following Him, … and some of them were laughing, some were dancing, … and some singing. … Some of them were falling on the ground offering obeisances to the Lord.” Speaking and pausing, clicking the switch on and off, he would sit straight, sometimes gently rocking and nodding his head as he urged forward his words. Or he would bend low over his books, carefully studying them through his reading glasses.

|  | An hour passed, and Prabhupāda worked on. The building was dark except for Prabhupāda’s lamp and quiet except for the sound of his voice and the click and hum of the dictating machine. He wore a faded peach turtleneck jersey beneath his gray wool cādara, and since he had just risen from bed, his saffron dhotī was wrinkled. Without having washed his face or gone to the bathroom he sat, absorbed in his work. At least for these few rare hours, the street and the Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa temple were quiet.

|  | This situation – with the night dark, the surroundings quiet, and him at his transcendental literary work – was not much different from his early-morning hours in his room at the Rādhā-Dāmodara temple in Vṛndāvana, India. There, of course, he had had no dictating machine, but he had worked during the same hours and from the same text, Caitanya-caritāmṛta. Once he had begun a verse-by-verse translation with commentary, and another time he had written essays on the text. Now, having just arrived in this corner of the world, so remote from the scenes of Lord Caitanya’s pastimes, he was beginning the first chapter of a new English version of Caitanya-caritāmṛta. He called it Teachings of Lord Caitanya.

|  | He was following what had become a vital routine in his life: rising early and writing the paramparā message of Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Putting aside all other considerations, disregarding present circumstances, he would merge into the timeless message of transcendental knowledge. This was his most important service to Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. The thought of producing more books and distributing them widely inspired him to rise every night and translate.

|  | Prabhupāda worked until dawn. Then he stopped and prepared himself to go down to the temple for the morning meeting.

|  | Though some of the New York disciples had objected, Śrīla Prabhupāda was still scheduled for the Mantra-Rock Dance at the Avalon Ballroom. It wasn’t proper, they had said, for the devotees out in San Francisco to ask their spiritual master to go to such a place. It would mean amplified guitars, pounding drums, wild light shows, and hundreds of drugged hippies. How could his pure message be heard in such a place?

|  | But in San Francisco Mukunda and others had been working on the Mantra-Rock Dance for months. It would draw thousands of young people, and the San Francisco Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa Temple stood to make thousands of dollars. So although among his New York disciples Śrīla Prabhupāda had expressed uncertainty, he now said nothing to deter the enthusiasm of his San Francisco followers.

|  | Sam Speerstra, Mukunda’s friend and one of the Mantra-Rock organizers, explained the idea to Hayagrīva, who had just arrived from New York: “There’s a whole new school of San Francisco music opening up. The Grateful Dead have already cut their first record. Their offer to do this dance is a great publicity boost just when we need it.”

|  | “But Svāmīji says that even Ravi Shankar is māyā,” Hayagrīva said.

|  | “Oh, it’s all been arranged,” Sam assured him. “All the bands will be onstage, and Allen Ginsberg will introduce Svāmīji to San Francisco. Svāmīji will talk and then chant Hare Kṛṣṇa, with the bands joining in. Then he leaves. There should be around four thousand people there.”

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda knew he would not compromise himself; he would go, chant, and then leave. The important thing was to spread the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa. If thousands of young people gathering to hear rock music could be engaged in hearing and chanting the names of God, then what was the harm? As a preacher, Prabhupāda was prepared to go anywhere to spread Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Since chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa was absolute, one who heard or chanted the names of Kṛṣṇa – anyone, anywhere, in any condition – could be saved from falling to the lower species in the next life. These young hippies wanted something spiritual, but they had no direction. They were confused, accepting hallucinations as spiritual visions. But they were seeking genuine spiritual life, just like many of the young people on the Lower East Side. Prabhupāda decided he would go; his disciples wanted him to, and he was their servant and the servant of Lord Caitanya.

|  | Mukunda, Sam, and Harvey Cohen had already met with rock entrepreneur Chet Helms, who had agreed that they could use his Avalon Ballroom and that, if they could get the bands to come, everything above the cost for the groups, the security, and a few other basics would go as profit for the San Francisco Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa Temple. Mukunda and Sam had then gone calling on the music groups, most of whom lived in the Bay Area, and one after another the exciting new San Francisco rock bands – the Grateful Dead, Moby Grape, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service – had agreed to appear with Svāmī Bhaktivedanta for the minimum wage of $250 per group. And Allen Ginsberg had agreed. The lineup was complete.

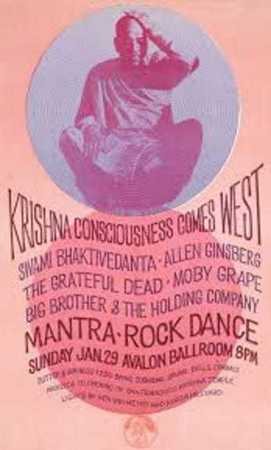

|  | In San Francisco every rock concert had an art poster, many of them designed by the psychedelic artist called Mouse. One thing about Mouse’s posters was that it was difficult to tell where the letters left off and the background began. He used dissonant colors that made his posters seem to flash on and off. Borrowing from this tradition, Harvey Cohen had created a unique poster – KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS COMES WEST – using red and blue concentric circles and a candid photo of Svāmīji smiling in Tompkins Square Park. The devotees put the posters up all over town.

|  | Hayagrīva and Mukunda went to discuss the program for the Mantra-Rock Dance with Allen Ginsberg. Allen was already well known as an advocate of the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra; in fact, acquaintances would often greet him with “Hare Kṛṣṇa!” when he walked on Haight Street. And he was known to visit and recommend that others visit the Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa Temple. Hayagrīva, whose full beard and long hair rivaled Allen’s, was concerned about the melody Allen would use when he chanted with Svāmīji. “I think the melody you use,” Hayagrīva said, “is too difficult for good chanting.”

|  | “Maybe,” Allen admitted, “but that’s the melody I first heard in India. A wonderful lady saint was chanting it. I’m quite accustomed to it, and it’s the only one I can sing convincingly.”

|  | With only a few days remaining before the Mantra-Rock Dance, Allen came to an early-morning kīrtana at the temple and later joined Śrīla Prabhupāda upstairs in his room. A few devotees were sitting with Prabhupāda eating Indian sweets when Allen came to the door. He and Prabhupāda smiled and exchanged greetings, and Prabhupāda offered him a sweet, remarking that Mr. Ginsberg was up very early.

|  | “Yes,” Allen replied, “the phone hasn’t stopped ringing since I arrived in San Francisco.”

|  | “That is what happens when one becomes famous,” said Prabhupāda. “That was the tragedy of Mahatma Gandhi also. Wherever he went, thousands of people would crowd about him, chanting, ‘Mahatma Gandhi kī jaya! Mahatma Gandhi kī jaya!’ The gentleman could not sleep.”

|  | “Well, at least it got me up for kīrtana this morning,” said Allen.

|  | “Yes, that is good.”

|  | The conversation turned to the upcoming program at the Avalon Ballroom. “Don’t you think there’s a possibility of chanting a tune that would be more appealing to Western ears?” Allen asked.

|  | “Any tune will do,” said Prabhupāda. “Melody is not important. What is important is that you will chant Hare Kṛṣṇa. It can be in the tune of your own country. That doesn’t matter.”

|  | Prabhupāda and Allen also talked about the meaning of the word hippie, and Allen mentioned something about taking LSD. Prabhupāda replied that LSD created dependence and was not necessary for a person in Kṛṣṇa consciousness. “Kṛṣṇa consciousness resolves everything,” Prabhupāda said. “Nothing else is needed.”

|  | At the Mantra-Rock Dance there would be a multimedia light show by the biggest names in the art, Ben Van Meter and Roger Hillyard. Ben and Roger were expert at using simultaneous strobe lights, films, and slide shows to fill an auditorium with optical effects reminiscent of LSD visions. Mukunda had given them many slides of Kṛṣṇa to use during the kīrtana. One evening, Ben and Roger came to see Svāmīji in his apartment.

|  | Roger Hillyard: He was great. I was really impressed. It wasn’t the way he looked, the way he acted, or the way he dressed, but it was his total being. Svāmīji was very serene and very humorous, and at the same time obviously very wise and in tune, enlightened. He had the ability to relate to a lot of different kinds of people. I was thinking, “Some of this must be really strange for this person – to come to the United States and end up in the middle of Haight-Ashbury with a storefront for an āśrama and a lot of very strange people around.” And yet he was totally right there, right there with everybody.

|  | On the night of the Mantra-Rock Dance, while the stage crew set up equipment and tested the sound system and Ben and Roger organized their light show upstairs, Mukunda and others collected tickets at the door. People lined up all the way down the street and around the block, waiting for tickets at $2.50 USD a piece. Attendance would be good, a capacity crowd, and most of the local luminaries were coming. LSD pioneer Timothy Leary arrived and was given a special seat onstage. Svāmī Kriyananda came, carrying a tamboura. A man wearing a top hat and a suit with a silk sash that said SAN FRANCISCO arrived, claiming to be the mayor. At the door, Mukunda stopped a respectably dressed young man who didn’t have a ticket. But then someone tapped Mukunda on the shoulder: “Let him in. It’s all right. He’s Owsley.” Mukunda apologized and submitted, allowing Augustus Owsley Stanley II, folk hero and famous synthesizer of LSD, to enter without a ticket.

|  | Almost everyone who came wore bright or unusual costumes: tribal robes, Mexican ponchos, Indian kurtās, “God’s-eyes,” feathers, and beads. Some hippies brought their own flutes, lutes, gourds, drums, rattles, horns, and guitars. The Hell’s Angels, dirty-haired, wearing jeans, boots, and denim jackets and accompanied by their women, made their entrance, carrying chains, smoking cigarettes, and displaying their regalia of German helmets, emblazoned emblems, and so on – everything but their motorcycles, which they had parked outside.

|  | The devotees began a warm-up kīrtana onstage, dancing the way Svāmīji had shown them. Incense poured from the stage and from the corners of the large ballroom. And although most in the audience were high on drugs, the atmosphere was calm; they had come seeking a spiritual experience. As the chanting began, very melodiously, some of the musicians took part by playing their instruments. The light show began: strobe lights flashed, colored balls bounced back and forth to the beat of the music, large blobs of pulsing color splurted across the floor, walls, and ceiling.

|  | A little after eight o’clock, Moby Grape took the stage. With heavy electric guitars, electric bass, and two drummers, they launched into their first number. The large speakers shook the ballroom with their vibrations, and a roar of approval rose from the audience.

|  | Around nine-thirty, Prabhupāda left his Frederick Street apartment and got into the back seat of Harvey’s Cadillac. He was dressed in his usual saffron robes, and around his neck he wore a garland of gardenias, whose sweet aroma filled the car. On the way to the Avalon he talked about the need to open more centers.

|  | At ten o’clock Prabhupāda walked up the stairs of the Avalon, followed by Kīrtanānanda and Ranchor. As he entered the ballroom, devotees blew conchshells, someone began a drum roll, and the crowd parted down the center, all the way from the entrance to the stage, opening a path for him to walk. With his head held high, Prabhupāda seemed to float by as he walked through the strange milieu, making his way across the ballroom floor to the stage.

|  | Suddenly the light show changed. Pictures of Kṛṣṇa and His pastimes flashed onto the wall: Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna riding together on Arjuna’s chariot, Kṛṣṇa eating butter, Kṛṣṇa subduing the whirlwind demon, Kṛṣṇa playing the flute. As Prabhupāda walked through the crowd, everyone stood, applauding and cheering. He climbed the stairs and seated himself softly on a waiting cushion. The crowd quieted.

|  | Looking over at Allen Ginsberg, Prabhupāda said, “You can speak something about the mantra.”

|  | Allen began to tell of his understanding and experience with the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra. He told how Svāmīji had opened a storefront on Second Avenue and had chanted Hare Kṛṣṇa in Tompkins Square Park. And he invited everyone to the Frederick Street temple. “I especially recommend the early-morning kīrtanas,” he said, “for those who, coming down from LSD, want to stabilize their consciousness on reentry.”

|  | Prabhupāda spoke, giving a brief history of the mantra. Then he looked over at Allen again: “You may chant.”

|  | Allen began playing his harmonium and chanting into the microphone, singing the tune he had brought from India. Gradually more and more people in the audience caught on and began chanting. As the kīrtana continued and the audience got increasingly enthusiastic, musicians from the various bands came onstage to join in. Ranchor, a fair drummer, began playing Moby Grape’s drums. Some of the bass and other guitar players joined in as the devotees and a large group of hippies mounted the stage. The multicolored oil slicks pulsed, and the balls bounced back and forth to the beat of the mantra, now projected onto the wall: Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. As the chanting spread throughout the hall, some of the hippies got to their feet, held hands, and danced.

|  | Allen Ginsberg: We sang Hare Kṛṣṇa all evening. It was absolutely great – an open thing. It was the height of the Haight-Ashbury spiritual enthusiasm. It was the first time that there had been a music scene in San Francisco where everybody could be part of it and participate. Everybody could sing and dance rather than listen to other people sing and dance.

|  | Jānakī: People didn’t know what they were chanting for. But to see that many people chanting – even though most of them were intoxicated – made Svāmīji very happy. He loved to see the people chanting.

|  | Hayagrīva: Standing in front of the bands, I could hardly hear. But above all, I could make out the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa, building steadily. On the wall behind, a slide projected a huge picture of Kṛṣṇa in a golden helmet with a peacock feather, a flute in His hand.

|  | Then Śrīla Prabhupāda stood up, lifted his arms, and began to dance. He gestured for everyone to join him, and those who were still seated stood up and began dancing and chanting and swaying back and forth, following Prabhupāda’s gentle dance.

|  | Roger Segal: The ballroom appeared as if it was a human field of wheat blowing in the wind. It produced a calm feeling in contrast to the Avalon Ballroom atmosphere of gyrating energies. The chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa continued for over an hour, and finally everyone was jumping and yelling, even crying and shouting.

|  | Someone placed a microphone before Śrīla Prabhupāda, and his voice resounded strongly over the powerful sound system. The tempo quickened. Śrīla Prabhupāda was perspiring profusely. Kīrtanānanda insisted that the kīrtana stop. Svāmīji was too old for this, he said; it might be harmful. But the chanting continued, faster and faster, until the words of the mantra finally became indistinguishable amidst the amplified music and the chorus of thousands of voices.

|  | Then suddenly it ended. And all that could be heard was the loud hum of the amplifiers and Śrīla Prabhupāda’s voice, ringing out, offering obeisances to his spiritual master: “Oṁ Viṣṇupāda Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakācārya Aṣṭottara-śata Śrī Śrīmad Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Gosvāmī Mahārāja kī jaya! ... All glories to the assembled devotees!”

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda made his way offstage, through the heavy smoke and crowds, and down the front stairs, with Kīrtanānanda and Ranchor close behind him. Allen announced the next rock group.

|  | As Svāmīji left the ballroom and the appreciative crowd behind, he commented, “This is no place for a brahmacārī.”

|  | The next morning the temple was crowded with young people who had seen Svāmīji at the Avalon. Most of them had stayed up all night. Śrīla Prabhupāda, having followed his usual morning schedule, came down at seven, held kīrtana, and delivered the morning lecture.

|  | Later that morning, while riding to the beach with Kīrtanānanda and Hayagrīva, Svāmīji asked how many people had attended last night’s kīrtana. When they told him, he asked how much money they had made, and they said they weren’t sure but it was approximately fifteen hundred dollars.

|  | Half-audibly he chanted in the back seat of the car, looking out the window as quiet and unassuming as a child, with no indication that the night before he had been cheered and applauded by thousands of hippies, who had stood back and made a grand aisle for him to walk in triumph across the strobe-lit floor amid the thunder of the electric basses and pounding drums of the Avalon Ballroom. For all the fanfare of the night before, he remained untouched, the same as ever in personal demeanor: he was aloof, innocent, and humble, while at the same time appearing very grave and ancient. As Kīrtanānanda and Hayagrīva were aware, Svāmīji was not of this world. They knew that he, unlike them, was always thinking of Kṛṣṇa.

|  | They walked with him along the boardwalk, near the ocean, with its cool breezes and cresting waves. Kīrtanānanda spread the cādara over Prabhupāda’s shoulders. “In Bengali there is one nice verse,” Prabhupāda remarked, breaking his silence. “I remember. ‘Oh, what is that voice across the sea calling, calling: Come here, come here. …’ ” Speaking little, he walked the boardwalk with his two friends, frequently looking out at the sea and sky. As he walked he softly sang a mantra that Kīrtanānanda and Hayagrīva had never heard before: “Govinda jaya jaya, gopāla jaya jaya, rādhā-ramaṇa hari, govinda jaya jaya.” He sang slowly, in a deep voice, as they walked along the boardwalk. He looked out at the Pacific Ocean: “Because it is great, it is tranquil.”

|  | “The ocean seems to be eternal,” Hayagrīva ventured.

|  | “No,” Prabhupāda replied. “Nothing in the material world is eternal.”

|  | In New York, since there were so few women present at the temple, people had inquired whether it were possible for a woman to join the Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement. But in San Francisco that question never arose. Most of the men who came to learn from Svāmīji came with their girlfriends. To Prabhupāda these boys and girls, eager for chanting and hearing about Kṛṣṇa, were like sparks of faith to be fanned into steady, blazing fires of devotional life. There was no question of his asking the newcomers to give up their girlfriends or boyfriends, and yet he uncompromisingly preached, “no illicit sex.” The dilemma, however, seemed to have an obvious solution: marry the couples in Kṛṣṇa consciousness.

|  | Because traditionally a sannyāsī would never arrange or perform marriages, by Indian standards someone might criticize Prabhupāda for allowing any mingling of the sexes. But Prabhupāda gave priority to spreading Kṛṣṇa consciousness. What Indian, however critical, had ever tried to transplant the essence of India’s spiritual culture into the Western culture? Prabhupāda saw that to change the American social system and completely separate the men from the women would not be possible. But to compromise his standard of no illicit sex was also not possible. Therefore, Kṛṣṇa conscious married life, the gṛhastha-āśrama, would be the best arrangement for many of his new aspiring disciples. In Kṛṣṇa consciousness husband and wife could live together and help one another in spiritual progress. It was an authorized arrangement for allowing a man and woman to associate. If as spiritual master he found it necessary to perform marriages himself, he would do it. But first these young couples would have to become attracted to Kṛṣṇa consciousness.

|  | Joan Campanella had grown up in a wealthy suburb of Portland, Oregon, where her father was a corporate tax attorney. She and her sister had had their own sports cars and their own boats for sailing on Lake Oswego. Disgusted by the sorority life at the University of Oregon, Joan had dropped out during her first term and enrolled at Reed College, where she had studied ceramics, weaving, and calligraphy. In 1963, she had moved to San Francisco and become the co-owner of a ceramics shop. Although she had then had many friends among fashionable shopkeepers, folksingers, and dancers, she had remained aloof and introspective.

|  | It was through her sister Jan that Joan had first met Śrīla Prabhupāda. Jan had gone with her boyfriend Michael Grant to live in New York City, where Michael had worked as a music arranger. In 1965 they had met Svāmīji while he was living alone on the Bowery, and they had become his initiated disciples (Mukunda and Jānakī). Svāmīji had asked them to get married, and they had invited Joan to the wedding. As a wedding guest for one day, Joan had then briefly entered Svāmīji’s transcendental world at 26 Second Avenue, and he had kept her busy all day making dough and filling kacaurī pastries for the wedding feast. Joan had worked in one room, and Svāmīji had worked in the kitchen, although he had repeatedly come in and guided her in making the kacaurīs properly, telling her not to touch her clothes or body while cooking and instructing her not to smoke cigarettes, because the food was to be offered to Lord Kṛṣṇa and therefore had to be prepared purely. Joan had been convinced by this brief association that Svāmīji was a great spiritual teacher, but she had returned to San Francisco without pursuing Kṛṣṇa consciousness further.

|  | A few months later, Mukunda and Jānakī had driven to the West Coast with plans of going soon to India but had changed their plans when Mukunda had received a letter from Svāmīji asking him to try to start a Kṛṣṇa conscious temple in California. Mukunda had talked about Svāmīji to Joan and other friends, and he had found that a lot of young people were interested. Joan had then accompanied Mukunda, Jānakī, and a boy named Roger Segal to the mountains in Oregon, where they had visited their mutual friends Sam and Marjorie, who had been living in a forest lookout tower.

|  | Mukunda had explained what he had known of Kṛṣṇa consciousness, and the six of them had begun chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa together. They had been especially interested in Svāmīji’s teachings about elevating consciousness without drugs. Mukunda had talked excitedly about Svāmīji’s having asked him to start a temple in California, and soon he and his wife, Jānakī; Sam and his girlfriend Marjorie; and Roger and Joan, now intimate friends, had moved to an apartment in San Francisco to find a storefront and set the stage for Svāmīji.

|  | After Svāmīji’s arrival, Joan had begun attending the temple kīrtanas. She felt drawn to Svāmīji and the chanting, and she especially liked the informal visiting hours. Svāmīji would sit in his rocking chair with his hand in his bead bag, chanting the holy names, and Joan would sit fascinated, watching his fingers moving within the bag.

|  | One day during Svāmīji’s visiting hours, while Svāmīji was sitting in his rocking chair and Joan and others were sitting at his feet, Jānakī’s cat crept in through the hallway door and began slowly coming down the hallway. The cat came closer and closer and slowly meandered right in front of Svāmīji’s feet. It sat down, looking up intently at Svāmīji, and began to meow. None of the devotees knew what to expect. Svāmīji began gently stroking the back of the cat with his foot, saying, “Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa. Are you feeding him prasādam milk?”

|  | Joan: I was touched by Svāmīji’s activities and his kindness – even to cats – and I longed for more association with him.

|  | Joan came to understand that serving Svāmīji was a serious matter. But she didn’t want to jump into initiation until she was one-hundred-percent sure about it. Sometimes she would cry in ecstasy, and sometimes she would fall asleep during Svāmīji’s lecture. So she remained hesitant and skeptical, wondering, “How can I actually apply Svāmīji’s teachings to my life?”

|  | One evening Svāmīji asked her, “When are you going to be initiated?” Joan said that she didn’t know but that she relished reading his books and chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa. She said that because she was attracted to the mountains and to elevated spiritual consciousness, she wanted to travel to Tibet.

|  | Svāmīji, sitting in his rocking chair, looked down at Joan as she sat at his feet. She felt he was looking right through her. “I can take you to a higher place than Tibet,” he said. “Just see.”

|  | Joan suddenly felt that Svāmīji knew everything about her, and she understood, “Oh, I have to see through his eyes what Kṛṣṇa consciousness is.” He was promising that he would take her to some very elevated realm, but she would have to see it. It was then that Joan decided to become Svāmīji’s disciple.

|  | When she told her boyfriend Roger, he was astounded. He and Joan had been coming to the kīrtanas and lectures together, but he still had doubts. Maybe it would be good for him and Joan to get married but not initiated. Joan, however, was more determined. She explained to Roger that Svāmīji hadn’t come just to perform marriages; you had to get initiated first.

|  | Roger Segal had grown up in New York. He was following a haṭha-yoga guru, had experimented with psychedelic chemicals, and had traveled in the Deep South as a civil rights activist, taking part in freedom marches with the blacks. Large-bodied, sociable, and outgoing, he had lots of friends in San Francisco. At the airport, in a merry mood with the Haight-Ashbury crowd, he had seen Svāmīji for the first time and been especially struck by Svāmīji’s regal bearing and absence of self-consciousness. The concept of reincarnation had always intrigued him, but after attending some of Svāmīji’s lectures and hearing him explain transmigration of the soul, he felt he had found someone who definitely knew the answer to any question about life after death.

|  | One night, after attending the program at the temple, Roger returned to his apartment and sat down on the fire escape to meditate on what Svāmīji had said. The world is false, he had said. “But it feels real to me,” Roger thought. “If I pinch my arm, I feel pain. So how is that illusion? This fire escape is real; otherwise I would be falling in space. This space is real, isn’t it?”

|  | Roger decided he didn’t understand what Svāmīji meant by illusion. “If I try to walk through the wall,” he thought, “would that be real or not? Maybe the wall’s reality is just in my mind.” To test the illusion he went inside his apartment, concentrated his mind, and walked against the wall – smack. He sat down again and thought, “What does Svāmīji mean when he says that the world is illusion?” He decided he should ask at the next meeting.

|  | He did. And Śrīla Prabhupāda told him that actually the world is real, because it was created by God, the supreme reality. But it is unreal in the sense that everything material is temporary. When a person takes the temporary world to be permanent and all in all, he is in illusion. Only the spiritual world, Svāmīji explained, is eternal and therefore real.

|  | Roger was satisfied by Svāmīji’s answer. But he had other difficulties: he thought Svāmīji too conservative. When Svāmīji said that people’s dogs must be kept outside the temple, Roger didn’t like it. Many visitors brought pet dogs with them to the temple, and now there was a hitching post in front of the building just to accommodate the pets on leashes. But Svāmīji wouldn’t allow any pets inside. “This philosophy is for humans,” he said. “A cat or dog cannot understand it, although if he hears the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa he can receive a higher birth in the future.”

|  | Roger also had other points of contention with what he considered Svāmīji’s conservative philosophy. Svāmīji repeatedly spoke against uncontrolled habits like smoking, but Roger couldn’t imagine giving up such things. And the instructions about restricting sex life especially bothered him. Yet despite his not following very strictly, Roger felt himself developing a love for Svāmīji and Kṛṣṇa. He sensed that Svāmīji had much to teach him and that Svāmīji was doing it in a certain way and a certain order. Roger knew that Svāmīji saw him as a baby in spiritual life who had to be spoon-fed; he knew he had to become submissive and accept whatever Svāmīji gave him.

|  | Sam Speerstra, tall and slender with curly reddish-gold hair, was athletic (he had trained as an Olympic skier) yet artistic (he was a writer and wood sculptor). He had graduated from Reed College in Oregon and gone on as a Fulbright scholar to a small college in Switzerland, where he had obtained an M.A. in philosophy. He was popular – as Mukunda saw him, “the epitome of the rugged individualist.”

|  | When Mukunda had visited Sam at his mountain lookout tower and told him about Svāmīji and Kṛṣṇa consciousness, Sam had been intrigued by the new ideas. Sam’s life had nearly reached a dead end, but he had seen hope in what Mukunda and Jānakī had been saying about Svāmīji. After spending only a few days with Mukunda, Sam had been eager to help him establish a temple of Kṛṣṇa consciousness in San Francisco.

|  | Sam was the one who knew the local rock stars and had persuaded them to appear at the Avalon with Svāmī Bhaktivedanta, whom he had never met. Sam had seen Svāmīji for the first time when Svāmīji had arrived at the San Francisco airport; and Sam had later insisted that he had seen a flash of light come from Svāmīji’s body.

|  | At first Sam had been afraid to say anything, nor had he known what to say – Prabhupāda was completely new to him and seemed so elevated. But the day after the program at the Avalon, when Mukunda told Prabhupāda that Sam had arranged the dance, Prabhupāda sent for him to find out how much money they had made. Sitting across from Prabhupāda, who sat behind his small desk, Sam informed him that they had made about fifteen hundred dollars profit. “Well then,” Śrīla Prabhupāda said, “you will be the treasurer.” Then Śrīla Prabhupāda asked him, “What is your idea of God?”

|  | “God is one,” Sam replied.

Prabhupāda asked, “What is the purpose of worshiping God?”

Sam replied, “To become one with God.”

|  | “No,” Prabhupāda said. “You cannot become one with God. God and you are always two different individuals. But you can become one in interest with Him.” And then he told Sam about Kṛṣṇa. After they talked, Prabhupāda said, “You can come up every day, and I will teach you how to do books.” So Sam began meeting with Prabhupāda for half an hour a day to learn bookkeeping.

|  | Sam: I had never been very good at keeping books, and I really didn’t want to do it. But it was a good excuse to come and see Svāmīji every day. He would chew me out when I would spend too much money or when I couldn’t balance the books properly. I really loved the idea that he was so practical that he knew bookkeeping. He became so much more of a friend from the beginning, rather than some idealized person from another sphere of life. I took almost all my practical questions to him. I learned to answer things for myself based on the way Svāmīji always answered day-to-day problems. And the first thing he made me do was to get married to my girlfriend.

|  | Mukunda and his wife, Jānakī, whose apartment was just down the hall from Śrīla Prabhupāda’s, were the only couple Śrīla Prabhupāda had already initiated and married. Mukunda, who often wore his strand of large red japa beads in two loose loops around his neck, had grown long hair and a short, thick black beard since coming to San Francisco. He had entered the “summer of love” spirit of Haight-Ashbury and was acquainted with many of the popular figures. Although occasionally earning money as a musician, he spent most of his time promoting Prabhupāda’s mission, especially by meeting people to arrange gala programs like the one at the Avalon. He was a leader in bringing people to assist Prabhupāda, yet he had no permanent sense of commitment. He was helping because it was fun. Having little desire to be different from his many San Francisco friends, he did not strictly follow Prabhupāda’s principles for regulated spiritual life.

|  | In his exchanges with Śrīla Prabhupāda, Mukunda liked to assume a posture of fraternal camaraderie rather than one of menial servitude, and Śrīla Prabhupāda reciprocated. Sometimes, however, Prabhupāda would assert himself as the teacher. Once when Prabhupāda walked into Mukunda’s apartment, he noticed a poster on the wall showing a matador with a cape and sword going after a bull. “This is a horrible picture!” Śrīla Prabhupāda exclaimed, his face showing displeasure. Mukunda looked at the poster, realizing for the first time what it meant. “Yes, it is horrible,” he said, and tore it off the wall.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda was eager to have someone play the mṛdaṅga properly during the kīrtanas, and Mukunda, a musician, was a likely candidate.

|  | Mukunda: The day the drum came I asked Svāmīji if I could learn, and he said yes. I asked him when, and he said, “When do you want?” “Now?” I asked. He said, “Yes.” I was a little surprised to get such a quick appointment. But I brought the drum to his room, and he began to show me the basic beat. First there was gee ta ta, gee ta ta, gee ta ta. And then one slightly more complicated beat, gee ta ta, gee ta ta, gee ta ta geeeee ta.

|  | As I began to play the beat, I kept speeding it up, and he kept telling me to slow down. He spent a lot of time just showing me how to strike the heads of the drum. Then I finally began to get it a little. But he had to keep admonishing me to slow down and pronounce the syllables as I hit the drum – gee ta ta. The syllables, he said, and the drum should sound the same. I should make it sound like that and always pronounce them.

|  | I was determined and played very slowly for a long, long time. I was concentrating with great intensity. Then suddenly I was aware of Svāmīji standing motionless beside me. I didn’t know how long he was going to stand there without saying anything, and I became a little uncomfortable. But I continued playing. When I got up the courage to look up and see his face, to my surprise he was moving his head back and forth in an affirming way with his eyes closed. He seemed to be enjoying the lesson. This came as a complete surprise to me. Although I had taken music lessons before and had spent many years taking piano lessons, I can never remember an instance when the teacher seemed to actually enjoy my playing. I felt very wonderful to see that here was a teacher who was so perfect, who enjoyed what he was teaching so much, not because it was his personal teaching or his personal method, but because he was witnessing Kṛṣṇa’s energy pass through him to a conditioned soul like myself. And he was getting great pleasure out of it. I had a deeper realization that Svāmīji was a real teacher, although I had no idea what a spiritual master really was.

|  | To Mukunda’s wife, Jānakī, Kṛṣṇa consciousness meant dealing in a personal way with Svāmīji. As long as he was around she was all right. She enjoyed asking him questions, serving him, and learning from him how to cook. She didn’t care much for studying the philosophy of Kṛṣṇa consciousness, but she quickly developed an intense attraction for him.

|  | Jānakī: There were a group of us sitting around in Svāmīji’s apartment, and I asked him if he had any children. He looked at me as if I had said something strange, and he said, “You are not my child?” I said, “Well, yes.” And he said, “Are not all these my children?” And his answer was so quick that I never doubted that he seriously meant what he said.

|  | For several hours each morning Prabhupāda showed Jānakī, Joan, and others how to cook. One day in the kitchen he noticed a kind of berry he had never tasted, and he asked Jānakī what they were. She told him strawberries. He immediately popped one into his mouth, saying, “That’s very tasty.” And he proceeded to eat another and another, exclaiming, “Very tasty!”

|  | One time Jānakī was making whipped cream when Prabhupāda came into the kitchen and asked, “What’s that?”

She replied, “It’s whipped cream.”

“What is whipped cream?” he asked.

“It’s cream,” she replied, “but when you beat it, it fluffs up into a more solid form.”

|  | Aunque siempre insistió en las reglas de la cocina (una de las más importantes es que nadie podía comer en la cocina), Śrīla Prabhupāda inmediatamente sumergió su dedo en la crema batida y la probó. “Esto es yogur", dijo.

|  | In a lighthearted, reprimanding way that was her pleasure, Jānakī replied, “No, Svāmīji, it’s whipped cream.”

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda corrected her, “No, it is yogurt.” And again he put his finger into it and tasted it, saying, “Oh, it tastes very nice.”

|  | “Svāmīji!” Jānakī accused him. “You’re eating in the kitchen!” Śrīla Prabhupāda merely smiled and shook his head back and forth, saying, “That is all right.”

|  | Jānakī: One time I told him, “Svāmīji, I had the most exciting dream. We were all on a planet of our very own, and everybody from earth had come there. They had all become pure devotees, and they were all chanting. You were sitting on a very special chair high off the ground, and the whole earth was clapping and chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa.” Svāmīji smiled and said, “Oh, that’s such a lovely dream.”

|  | Bonnie McDonald, age nineteen, and her boyfriend Gary McElroy, twenty, had both come to San Francisco from Austin, where they had been living together as students at the University of Texas. Bonnie was a slight, fair blonde with a sweet southern drawl. She was born and raised in southeast Texas in a Baptist family. In high school she had become agnostic, but later, while traveling in Europe and studying the religious art there and the architecture of the great cathedrals, she had concluded that these great artists couldn’t have been completely wrong.

|  | Gary, the son of a U.S. Air Force officer, had been raised in Germany, Okinawa, and other places around the world before his family had settled in Texas. His dark hair and bushy brows gave him a scowling look, except when he smiled. He was one of the first students at the University of Texas to wear long hair and experiment with psychedelic drugs. While taking LSD together, he and Bonnie had become obsessed with the idea of going on a spiritual search, and without notifying their parents or school they had driven to the West Coast “in search of someone who could teach us about spiritual life.”

|  | They had spent a few frustrating months searching through spiritual books and amongst spiritual groups in Haight-Ashbury. They had become vegetarians. Gary had started teaching himself to play electric guitar while Bonnie had gone to Golden Gate Park every day to perform a self-styled haṭha-yoga meditation. But gradually they had become disillusioned and had felt themselves becoming degraded from drugs.

|  | When the disciple is ready, the guru will appear, they had read. And they had waited eagerly for the day when their guru would come. Although Bonnie had spent most of her time in the parks of San Francisco, one day she had been looking through a tableful of magazines in a Haight-Ashbury head shop when she had found a copy of Back to Godhead, the mimeographed journal produced by Śrīla Prabhupāda’s disciples in New York. She had been particularly attracted to Hayagrīva’s article about Svāmīji. The descriptions of Svāmīji’s smile, his bright eyes, his pointy-toed shoes, and the things he said had given her a feeling that this might be the guru she had been looking for. And when she had learned that this same Svāmīji had opened an āśrama in Haight-Ashbury, she had immediately started searching through the neighborhood until she had found the temple on Frederick Street.

|  | Before Bonnie and Gary met Svāmīji they had both been troubled. Gary was in anxiety about the threat of being drafted into the Army, and both of them were disillusioned because they had not found the truth they had come to San Francisco to find. So on meeting Śrīla Prabhupāda in his room they began to explain their situation.

|  | Bonnie: He was sitting in a rocking chair in his little apartment, and he looked at us like we were crazy – because we were – and said, “You come to my classes. Simply come to my classes every morning and every evening, and everything will be all right.” That sounded to us like an unbelievable panacea, but because we were so bewildered, we agreed to it.

|  | I told him I had traveled all over Europe, and he said, “Oh, you have traveled so much.” And I said to him, “Yes, I have traveled so much, I have done so many things, but none of it ever made me happy.” He was pleased with that statement. He said, “Yes, that is the problem.”

|  | We began going to his morning lectures. For us it was a long distance to get there at seven in the morning, but we did it every morning with the conviction that this was what he had said to do and we were going to do it. Then one day he asked us, “What do you do?” When we said that formerly we had been art students at college, he told us to paint pictures of Kṛṣṇa. Shortly after that, we asked to be initiated.

|  | Joan and Roger were soon initiated, receiving the names Yamunā and Gurudāsa. And the very next day they were married. At their wedding ceremony, Svāmīji presided, wearing a bulky garland of leaves and rhododendron flowers. He sat on a cushion on the temple floor, surrounded by his followers and paraphernalia for the sacrificial fire. Before him was the small mound of earth where he would later build the fire. He explained the meaning of Kṛṣṇa conscious marriage and how husband and wife should assist one another and serve Kṛṣṇa, keeping Him in the center. Svāmīji had commented that he did not like the Western women’s dress, and at his request, Yamunā was dressed in a sārī.

|  | Although Svāmīji had called for ghī (clarified butter) as one of the sacrificial ingredients, the devotees, thinking ghī too costly, had substituted melted margarine. He had called for firewood also, and the devotees had supplied him the bits of a broken orange crate. Now, with Yamunā and Gurudāsa seated before him on the opposite side of the mound of earth, he picked up a small piece of the splintered orange crate, dipped it into what was supposed to be ghī, and held it in the candle flame to begin the fire. The splinter flamed, sputtered, and went out. He picked up another splinter and moistened it in the melted margarine, but when he touched it to the flame it made the same svit-svit sound and sputtered out. After trying unsuccessfully four or five times, Svāmīji looked up and said, “This marriage will have a very slow start.” Yamunā began to cry.

|  | Bonnie and Gary were initiated just two weeks after they had met Svāmīji. Bonnie’s initiated name was Govinda dāsī, and Gary’s was Gaurasundara. Although still dressed in blue jeans, even at their initiation, and not professing to know much of what was going on, they had confidence in Svāmīji. They knew that their minds were still hazy from drugs, but they took their initiation seriously and became strict followers. Gaurasundara threw out whatever marijuana he had, and he and Govinda dāsī began eating only food they had offered to Lord Kṛṣṇa. Two weeks after their initiation, Svāmīji conducted their marriage ceremony.

|  | On the evening of the wedding Govinda dāsī’s father came from Texas, even though he objected to Kṛṣṇa consciousness as radically un-American. Walking up to Śrīla Prabhupāda’s seat in the temple, Govinda dāsī’s father asked, “Why do ya have to change my daughter’s name? Why does she have to have an Indian name?”

|  | Prabhupāda looked at him and then, with a mischievous gleam, looked at Mr. Patel, an Indian guest standing nearby with his family. “You don’t like Indians?” he asked.

|  | Everyone who heard Svāmīji laughed – except for Govinda dāsī’s father, who replied, “Well, yeah, they’re all right. But why does Bonnie have to have a different name?”

|  | “Because she has asked me to give her one,” Śrīla Prabhupāda replied. “If you love her, you will like what she likes. Your daughter is happy. Why do you object?” The discussion ended there, and Govinda dāsī’s father remained civil. Later he enjoyed taking prasādam with his daughter and son-in-law.

|  | Govinda dāsī: Gaurasundara and I set about reading the three volumes of Svāmīji’s Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. And at the same time Svāmīji had told me to paint a large canvas of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa and a cow. So every day for the whole day I would paint, and Gaurasundara would read out loud from the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam – one volume after another. We did this continuously for two months. During this time Svāmīji also asked me to do a portrait of him standing before a background painting of Lord Caitanya dancing. Svāmīji wanted it so that Lord Caitanya’s foot would be touching his head. I tried. It was a pretty horrible painting, and yet he was happy with it.

|  | Prabhupāda’s thoughtful followers felt that some of the candidates for initiation did not intend to fulfill the exclusive lifelong commitment a disciple owes to his guru. “Svāmīji,” they would say, “some of these people come only for their initiation. We have never seen them before, and we never see them again.” Śrīla Prabhupāda replied that that was the risk he had to take. One day in a lecture in the temple, he explained that although the reactions for a disciple’s past sins are removed at initiation, the spiritual master remains responsible until the disciple is delivered from the material world. Therefore, he said, Lord Caitanya warned that a guru should not accept many disciples.

|  | One night in the temple during the question-and-answer session, a big, bearded fellow raised his hand and asked Prabhupāda, “Can I become initiated?”

|  | The brash public request annoyed some of Prabhupāda’s followers, but Prabhupāda was serene. “Yes,” he replied. “But first you must answer two questions. Who is Kṛṣṇa?”

|  | The boy thought for a moment and said, “Kṛṣṇa is God.”

“Yes,” Prabhupāda replied. “And who are you?”

Again the boy thought for a few moments and then replied, “I am the servant of God.”

“Very good,” Prabhupāda said. “Yes, you can be initiated tomorrow.”

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda knew that it would be difficult for his Western disciples to stick to Kṛṣṇa consciousness and attain the goal of pure devotional service. All their lives they had had the worst of training, and despite their nominal Christianity and philosophical searching, most of them knew nothing of the science of God. They did not even know that illicit sex and meat-eating were wrong, although when he told them they accepted what he said. And they freely chanted Hare Kṛṣṇa. So how could he refuse them?

|  | Of course, whether they would be able to persevere in Kṛṣṇa consciousness despite the ever-present attractions of māyā would be seen in time. Some would fall – that was the human tendency. But some would not. At least those who sincerely followed his instructions to chant Hare Kṛṣṇa and avoid sinful activities would be successful. He gave the example that a person could say that today’s fresh food, if not properly used, would spoil in a few days. But if it is fresh now, to say that in the future it will be misused and therefore spoil is only a surmise. Yes, in the future anyone could fall down. But Prabhupāda took it as his responsibility to engage his disciples now. And he was giving them the methods which if followed would protect them from ever falling down.

|  | Aside from Vedic standards, even by the standard of Svāmīji’s New York disciples the devotees in San Francisco were not very strict. Some continued going to the doughnut shop, eating food without offering it to Kṛṣṇa, and eating forbidden things like chocolate and commercial ice cream. Some even indulged in after-kīrtana cigarette breaks right outside the temple door. Some got initiated without knowing precisely what they had agreed to practice.

|  | Kīrtanānanda: The mood in San Francisco was a lot more relaxed. The devotees liked to go to the corner and have their coffee and doughnuts. But Prabhupāda loved the way so many people were coming. And he loved the program at the Avalon Ballroom. But there were two sides: those who strictly followed the rules and regulations and emphasized purity and then those who were not so concerned about strictness but who wanted to spread Kṛṣṇa consciousness as widely as possible. Svāmīji was so great that he embraced both groups.

|  | Michael Wright, twenty-one, had recently gotten out of the Marine Corps, and Nancy Grindle, eighteen, was fresh out of high school. They had met in college in Los Angeles. Feeling frustrated and in need of something tangible to which to dedicate their lives, they had come to San Francisco to join the hippies. But they soon realized that they and the Haight-Ashbury hippies, whom they found dirty, aimless, unproductive, and lost in their search for identity, had little in common. So Nancy took a job as a secretary for the telephone company, and Michael found work as a lineman for the electric company. Then they heard about the Svāmī in Haight-Ashbury and decided to visit the temple.

|  | It was an evening kīrtana, and the irrepressible hippies were twirling, twisting, and wiggling. Michael and Nancy took a seat on the floor off to one side, impressed more by the presence of the Svāmī than by the kīrtana. After the kīrtana Prabhupāda lectured, but they found his accent heavy. They wanted to understand – they had an innate feeling that he was saying something valuable – and yet the secrets seemed locked behind a thick accent and within a book written in another language. They decided to come back in the morning and try again.

|  | At the morning program they found a smaller group: a dozen devotees with beads for chanting draped around their necks, a few street people. The kīrtana seemed sweeter and more mellow, and Michael and Nancy chanted and danced along with the devotees. Then Prabhupāda spoke, and this time they caught a few of his ideas. They stayed for breakfast and became friends with Mukunda and Jānakī, Sam and Marjorie (now Śyāmasundara and Mālatī), Yamunā and Gurudāsa, and Govinda dāsī and Gaurasundara. They liked the devotees and promised to come again that evening. Soon they were regularly attending the morning and evening programs, and Nancy, along with the other women, was attending Prabhupāda’s weekend cooking classes.

|  | Michael was open to Prabhupāda’s ideas, but he had difficulty accepting the necessity of surrendering to a spiritual authority. His tendency was to reject authorities. But the more he thought about it, the more he saw that Prabhupāda was right – he had to accept an authority. He reasoned, “Every time I stop at a red light, I’m accepting an authority.” And finally he concluded that to progress in spiritual understanding he would have to accept a spiritual authority. Yet because he didn’t want to accept it, he was in a dilemma. Finally, after hearing Prabhupāda’s lectures for two weeks, Michael decided to surrender to Prabhupāda’s authority and try to become Kṛṣṇa conscious.

|  | Michael: Nancy and I decided to get married and become Svāmīji’s disciples and members of his Society. We told some of the devotees, “We would like to see Svāmīji.” They said, “Yes, just go up. He’s on the third floor.” We were a little surprised that there were no formalities required, and when we got to the door his servant Ranchor let us in. We went in with our shoes on, so Ranchor had to ask us to take them off.

|  | I didn’t know exactly what to say to Svāmīji – I was depending on my future wife to make the initial opening – but then I finally said, “We came because we would like to become members of your Kṛṣṇa conscious Society.” He said this was very nice. Then I said that actually the main reason we were there was that we wanted to be married. We knew that he performed marriage ceremonies and that it was part of the Society’s requirements that couples had to be duly married before they could live together. Svāmīji asked me if I liked the philosophy and if I had a job. My answer to both questions was yes. He explained that first of all we would have to be initiated, and then we could be married the next month.

|  | At their initiation Michael received the name Dayānanda, and Nancy received the name Nandarāṇī. Soon Prabhupāda performed their marriage.

|  | Nandarāṇī: We knew it would be a very big wedding. In Haight-Ashbury, whenever Svāmīji would perform a wedding hundreds of people would come, and the temple would be filled. My parents were coming, and Dayānanda’s parents were also coming.

|  | Svāmīji said that it was proper that I cook. He said I should come to his apartment on the morning of the wedding and he would help me cook something for the wedding feast. So that morning I put on my best jeans and my best sweatshirt and my boots, and I went off to Svāmīji’s apartment. When I got upstairs I walked in with my boots on. Svāmīji was sitting there in his rocking chair. He smiled at me and said, “Oh, you have come to cook.” I said, “Yes.” He sat there and looked at me – one of those long silent stares. He said, “First take off the boots.”

|  | After I took off my boots and my old leather jacket, Svāmīji got up and went into the kitchen. He got a very large pot that had been burned so thick on the bottom that practically there was no metal visible. He handed it to me and said, “We want to boil milk in this pot. It has to be washed.”

|  | There wasn’t a sink in Svāmīji’s kitchen, only a teeny round basin. So I went into the bathroom, put the pot in the bathtub, and rinsed it out. I assumed Svāmīji didn’t want the black off the bottom, because it was burned on. So I brought it back to him, and he said, “Oh, that is very clean, but just take off this little black on the bottom here.”

|  | I said okay and got a knife and crawled into the bathtub and started scrubbing the black off. I worked and worked and worked, and I scrubbed and scrubbed. I had cleanser up to my elbows, and I made a mess everywhere. I had gotten about half the black off – the rest seemed to be more or less an integral part of the bottom – so I took the pot back to Svāmīji and said, “This is the best I can do. All of this is burned on.” He said, “Yes, yes, you’ve done a wonderful job. Now just take off this black that’s left.”

|  | So I went back into the bathtub and scrubbed and scrubbed and scrubbed. It was almost midday when I came out of the bathtub with all the black scrubbed off the bottom of that pot. He was so happy when I brought the pot in. It was sparkling. A big smile came on his face, and he said, “Oh, this is perfect.” I was exhausted.

|  | Then Svāmīji welcomed me into his kitchen and taught me how to make rasagullās. We boiled the milk, curdled it, and then I sat down and began rolling the curd into balls on a tray. As I rolled the balls I would put them in a little row along the tray. And every single ball had to be exactly the same size. Svāmīji would take his thumb and first and second fingers and shoot the balls out of the row when they weren’t the right size. And I would have to remake them until they were the right size. This went on until I had a full tray of balls all the same size.

|  | Then Svāmīji showed me how to boil the balls of curd in sugar water. Mālatī, Jānakī, and I were cooking in the kitchen, and Svāmīji was singing.

|  | At one point, Svāmīji stopped singing and asked me, “Do you know what your name means?” I couldn’t even remember what my name was. He had told me at initiation, but because none of us used our devotee names, I couldn’t remember what mine was. I said, “No, Svāmīji, what does my name mean?” He said, “It means you are the mother of Kṛṣṇa.” And he laughed loudly and went back to stirring the rasagullās. I couldn’t understand who Kṛṣṇa was, who in the world His mother would be, or how I was in any way related to her. But I was satisfied that Svāmīji felt that I was somebody worth being.

|  | I finished cooking that afternoon about four o’clock, and then I went home to get dressed for the wedding. Although I had never worn anything but old dresses and jeans, Svāmīji had suggested to the other ladies that they find a way to put me into a sārī for the wedding. So we bought a piece of silk to use for a sārī. I went to Mālatī’s house. She was going to try to help me put it on. I couldn’t keep it on, so she had to sew it on me. Then they decorated me with flowers and took me to Svāmīji and showed him. He was very happy. He said, “This is the way our women should always look. No more jeans and dresses. They should always wear sārīs.”

|  | Actually, I looked a fright – I kept stumbling, and they had had to sew the cloth on me – but Svāmīji thought it was wonderful. The cloth was all one color, so Svāmīji said, “Next time you should buy cloth that has a little border on the bottom, so it’s two colors. I like two colors better.”

|  | When we went downstairs to the wedding, Svāmīji met my relatives. He spoke to them very politely. My mother cried a lot during the ceremony. I was very satisfied that she had been blessed by meeting Svāmīji.

|  | Steve Bohlert, age twenty, born and raised in New York and now living the hippie life in San Francisco, had read in The Oracle about Svāmī Bhaktivedanta’s coming to San Francisco. The idea of meeting an Indian swami had interested him, and responding to a notice he had seen posted on Haight Street, he had gone along with Carolyn Gold, the woman he was living with, to the airport to meet Svāmī Bhaktivedanta. He and Carolyn had both gotten a blissful lift by chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa and seeing Prabhupāda, and they began regularly attending the lectures and kīrtanas at the temple. Steve decided he wanted to become like the Svāmī, so he and Carolyn went together to see Prabhupāda and request initiation. Speaking privately with Prabhupāda in his room, they discussed obedience to the spiritual master and becoming vegetarian. When Prabhupāda told them that they should either stop living together or get married, they said they would like to get married. An initiation date was set.

|  | Prabhupāda asked Steve to shave his long hair and beard. “Why do you want me to shave my head?” Steve protested. “Kṛṣṇa had long hair, Rāma had long hair, Lord Caitanya had long hair, and Christ had long hair. Why should I shave my head?”

|  | Prabhupāda smiled and replied, “Because now you are following me.” There was a print on the wall of Sūradāsa, a Vaiṣṇava. “You should shave your head like that,” Prabhupāda said, pointing to Sūradāsa.

|  | “I don’t think I’m ready to do that yet,” Steve said.

|  | “All right, you are still a young man. There is still time. But at least you should shave your face clean and cut your hair like a man.”

|  | On the morning of the initiation, Steve shaved off his beard and cut his hair around his ears so that it was short in front – but long in the back.

|  | “How’s this?” he asked.

|  | “You should cut the back also,” Prabhupāda replied. Steve agreed.

|  | To Steve Prabhupāda gave the name Subala and to Carolyn the name Kṛṣṇā-devī. A few days later he performed their wedding.

|  | Since each ceremony was another occasion for kīrtana and prasādam distribution, onlookers became attracted. And as the spiritual names and married couples increased with each ceremony, Prabhupāda’s spiritual family grew. The harmonious atmosphere was like that of a small, loving family, and Prabhupāda dealt with his disciples intimately, without the formalities of an institution or hierarchy.

|  | Disciples would approach him for various reasons, entering the little apartment to be alone with him as he sat on a mat before his makeshift desk in the morning sunlight. With men like Mukunda, Gurudāsa, and Śyāmasundara, Svāmīji was a friend. With Jānakī and Govinda dāsī he was sometimes ready to be chided, almost like their naughty son, or he would be their grandfatherly teacher of cooking, the enforcer of the rules of kitchen cleanliness. And to all of them he was the unfathomable pure devotee of Lord Kṛṣṇa who knew the conclusions of all the Vedic scriptures and who knew beyond all doubts the truth of transmigration. He could answer all questions. He could lead them beyond material life, beyond Haight-Ashbury hippiedom and into the spiritual world with Kṛṣṇa.

|  | It was 7:00 P.M. Śrīla Prabhupāda entered the temple dressed in a saffron dhotī, an old turtleneck jersey under a cardigan sweater, and a cādara around his shoulders. Walking to the dais in the rear of the room, he took his seat. The dais, a cushion atop a redwood plank two feet (60 cms.) off the floor, was supported between two redwood columns. In front of the dais stood a cloth-covered lectern with a bucket of cut flowers on either side. Covering the wall behind the dais was a typical Indian madras, with Haridāsa’s crude painting of Lord Caitanya in kīrtana hanging against it.