|

Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta

-

Volume 2 — Planting The Seed

<< 20 Stay High Forever >>

| “But while this was going on, an old man, one year past his allotted three score and ten, wandered into New York’s East Village and set about to prove to the world that he knew where God could be found. In only three months, the man, Svāmī A. C. Bhaktivedanta, succeeded in convincing the world’s toughest audience – Bohemians, acidheads, potheads, and hippies – that he knew the way to God: Turn Off, Sing Out, and Fall In. This new brand of holy man, with all due deference to Dr. Leary, has come forth with a brand of “Consciousness Expansion” that’s sweeter than acid, cheaper than pot, and nonbustible by fuzz. How is all this possible? “Through Kṛṣṇa,” the Svāmī says.”

— from The East Village Other, October 1966

|  | PRABHUPĀDA’S HEALTH WAS good that summer and fall, or so it seemed. He worked long and hard, and except for four hours of rest at night, he was always active. He would speak intensively on and on, never tiring, and his voice was strong. His smiles were strong and charming; his singing voice loud and melodious. During kīrtana he would thump Bengali mṛdaṅga rhythms on his bongo drum, sometimes for an hour. He ate heartily of rice, dāl, capātīs, and vegetables with ghī. His face was full and his belly protuberant. Sometimes, in a light mood, he would drum with two fingers on his belly and say that the resonance affirmed his good health. His golden color had the radiance of youth and well-being preserved by seventy years of healthy, nondestructive habits. When he smiled, virility and vitality came on so strong as to embarrass a faded, dissolute New Yorker. In many ways, he was not at all like an old man. And his new followers completely accepted his active youthfulness as a part of the wonder of Svāmīji, just as they had come to accept the wonder of the chanting and the wonder of Kṛṣṇa. Svāmīji wasn’t an ordinary man. He was spiritual. He could do anything. None of his followers dared advise him to slow down, nor did it ever really occur to them that he needed such protection – they were busy just trying to keep up with him.

|  | During the two months at 26 Second Avenue, he had achieved what had formerly been only a dream. He now had a temple, a duly registered society, full freedom to preach, and a band of initiated disciples. When a Godbrother had written asking him how he would manage a temple in New York, Prabhupāda had said that he would need men from India but that he might find an American or two who could help. That had been last winter. Now Kṛṣṇa had put him in a different situation: he had received no help from his Godbrothers, no big donations from Indian business magnates, and no assistance from the Indian government, but he was finding success in a different way. These were “happy days,” he said. He had struggled alone for a year, but then “Kṛṣṇa sent me men and money.”

|  | Yes, these were happy days for Prabhupāda, but his happiness was not like the happiness of an old man’s “sunset years,” as he fades into the dim comforts of retirement. His was the happiness of youth, a time of blossoming, of new powers, a time when future hopes expand without limit. He was seventy-one years old, but in ambition he was a courageous youth. He was like a young giant just beginning to grow. He was happy because his preaching was taking hold, just as Lord Caitanya had been happy when He had traveled alone to South India, spreading the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa. Prabhupāda’s happiness was that of a selfless servant of Kṛṣṇa to whom Kṛṣṇa was sending candidates for devotional life. He was happy to place the seed of devotion within their hearts and to train them in chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa, hearing about Kṛṣṇa, and working to spread Kṛṣṇa consciousness.

|  | Prabhupāda continued to accelerate. After the first initiations and the first marriage, he was eager for the next step. He was pleased by what he had, but he wanted to do more. It was the greed of the Vaiṣṇava – not a greed to have sense gratification but to take more and more for Kṛṣṇa. He would “go in like a needle and come out like a plow.” That is to say, from a small, seemingly insignificant beginning, he would expand his movement to tremendous proportions. At least, that was his desire. He was not content with his newfound success and security at 26 Second Avenue, but was yearning to increase ISKCON as far as possible. This had always been his vision, and he had written it into the ISKCON charter: “to achieve real unity and peace in the world … within the members, and humanity at large.”

|  | Svāmīji gathered his group together. He knew that once they tried it they would love it. But it would only happen if he personally went with them. Washington Square Park was only half a mile away, maybe a little more.

|  | Ravīndra-svarūpa: He never made a secret of what he was doing. He used to say, “I want everybody to know what we are doing.” Then one day, D-day came. He said, “We are going to chant in Washington Square Park.” Everybody was scared. You just don’t go into a park and chant. It seemed like a weird thing to do. But he assured us, saying, “You won’t be afraid when you start chanting. Kṛṣṇa will help you.” And so we trudged down to Washington Square Park, but we were very upset about it. Up until that time, we weren’t exposing ourselves. I was upset about it, and I know that several other people were, to be making a public figure of yourself.

|  | With Prabhupāda leading they set out on that fair Sunday morning, walking the city blocks from Second Avenue to Washington Square in the heart of Greenwich Village. And the way he looked – just by walking he created a sensation. None of the boys had shaved heads or robes, but because of Svāmīji – with his saffron robes, his white pointy shoes, and his shaved head held high – people were astonished. It wasn’t like when he would go out alone. That brought nothing more than an occasional second glance. But today, with a group of young men hurrying to keep up with him as he headed through the city streets, obviously about to do something, he caused a stir. Tough guys and kids called out names, and others laughed and made sounds. A year ago, in Butler, the Agarwals had been sure that Prabhupāda had not come to America for followers. “He didn’t want to make any waves,” Sally had thought. But now he was making waves, walking through the New York City streets, headed for the first public chanting in America, followed by his first disciples.

|  | In the park there were hundreds of people milling about – stylish, decadent Greenwich Villagers, visitors from other boroughs, tourists from other states and other lands – an amalgam of faces, nationalities, ages, and interests. As usual, someone was playing his guitar by the fountain, boys and girls were sitting together and kissing, some were throwing Frisbees, some were playing drums or flutes or other instruments, and some were walking their dogs, talking, watching everything, wandering around. It was a typical day in the Village.

|  | Prabhupāda went to a patch of lawn where, despite a small sign that read Keep Off the Grass, many people were lounging. He sat down, and one by one his followers sat beside him. He took out his brass hand cymbals and sang the mahā-mantra, and his disciples responded, awkwardly at first, then stronger. It wasn’t as bad as they had thought it would be.

|  | Jagannātha: It was a marvelous thing, a marvelous experience that Svāmīji brought upon me. Because it opened me up a great deal, and I overcame a certain shyness – the first time to chant out in the middle of everything.

|  | A curious crowd gathered to watch, though no one joined in. Within a few minutes, two policemen moved in through the crowd. “Who’s in charge here?” an officer asked roughly. The boys looked toward Prabhupāda. “Didn’t you see the sign?” an officer asked. Svāmīji furrowed his brow and turned his eyes toward the sign. He got up and walked to the uncomfortably warm pavement and sat down again, and his followers straggled after to sit around him. Prabhupāda continued the chanting for half an hour, and the crowd stood listening. A guru in America had never gone onto the streets before and sung the names of God.

|  | After kīrtana, he asked for a copy of the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam and had Hayagrīva read aloud from the preface. With clear articulation, Hayagrīva read: “Disparity in the human society is due to the basic principle of a godless civilization. There is God, the Almighty One, from whom everything emanates, by whom everything is maintained, and in whom everything is merged to rest. …” The crowd was still. Afterward, the Svāmī and his followers walked back to the storefront, feeling elated and victorious. They had broken the American silence.

|  | Allen Ginsberg lived nearby on East Tenth Street. One day he received a peculiar invitation in the mail:

|  | “Practice the transcendental sound vibration,

Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare

Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.

This chanting will cleanse the dust from the mirror of the mind.

International Society for Kṛṣṇa Consciousness

Meetings at 7 A.M. daily

Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 7:00 P.M.

You are cordially invited to come and bring your friends.”

|  | Svāmīji had asked the boys to distribute it around the neighborhood.

|  | One evening, soon after he received the invitation, Allen Ginsberg and his roommate, Peter Orlovsky, arrived at the storefront in a Volkswagen minibus. Allen had been captivated by the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra several years before, when he had first encountered it at the Kumbha-melā festival in Allahabad, India, and he had been chanting it often ever since. The devotees were impressed to see the world-famous author of Howl and leading figure of the beat generation enter their humble storefront. His advocation of free sex, marijuana, and LSD, his claims of drug-induced visions of spirituality in everyday sights, his political ideas, his exploration of insanity, revolt, and nakedness, and his attempts to create a harmony of likeminded souls – all were influential on the minds of American young people, especially those living on the Lower East Side. Although by middle-class standards he was scandalous and disheveled, he was, in his own right, a figure of worldly repute, more so than anyone who had ever come to the storefront before.

|  | Allen Ginsberg: Bhaktivedanta seemed to have no friends in America, but was alone, totally alone, and gone somewhat like a lone hippie to the nearest refuge, the place where it was cheap enough to rent.

|  | There were a few people sitting cross-legged on the floor. I think most of them were Lower East Side hippies who had just wandered in off the street, with beards and a curiosity and inquisitiveness and a respect for spiritual presentation of some kind. Some of them were sitting there with glazed eyes, but most of them were just like gentle folk – bearded, hip, and curious. They were refugees from the middle class in the Lower East Side, looking exactly like the street sādhus in India. It was very similar, that phase in American underground history. And I liked immediately the idea that Svāmī Bhaktivedanta had chosen the Lower East Side of New York for his practice. He’d gone to the lower depths. He’d gone to a spot more like the side streets of Calcutta than any other place.

|  | Allen and Peter had come for the kīrtana, but it wasn’t quite time – Prabhupāda hadn’t come down. They presented a new harmonium to the devotees. “It’s for the kīrtanas,” said Allen. “A little donation.” Allen stood at the entrance to the storefront, talking with Hayagrīva, telling him how he had been chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa around the world – at peace marches, poetry readings, a procession in Prague, a writers’ union in Moscow. “Secular kīrtana,” said Allen, “but Hare Kṛṣṇa nonetheless.” Then Prabhupāda entered. Allen and Peter sat with the congregation and joined in the kīrtana. Allen played harmonium.

|  | Allen: I was astounded that he’d come with the chanting, because it seemed like a reinforcement from India. I had been running around singing Hare Kṛṣṇa but had never understood exactly why or what it meant. But I was surprised to see that he had a different melody, because I thought the melody I knew was the melody, the universal melody. I had gotten so used to my melody that actually the biggest difference I had with him was over the tune – because I’d solidified it in my mind for years, and to hear another tune actually blew my mind.

|  | After the lecture, Allen came forward to meet Prabhupāda, who was still sitting on his dais. Allen offered his respects with folded palms and touched Prabhupāda’s feet, and Prabhupāda reciprocated by nodding his head and folding his palms. They talked together briefly, and then Prabhupāda returned to his apartment. Allen mentioned to Hayagrīva that he would like to come by again and talk more with Prabhupāda, so Hayagrīva invited him to come the next day and stay for lunch prasādam.

|  | Don’t you think Svāmīji is a little too esoteric for New York?” Allen asked. Hayagrīva thought. “Maybe,” he replied.

|  | Hayagrīva then asked Allen to help the Svāmī, since his visa would soon expire. He had entered the country with a visa for a two-month stay, and he had been extending his visa for two more months again and again. This had gone on for one year, but the last time he had applied for an extension, he had been refused. “We need an immigration lawyer,” said Hayagrīva. “I’ll donate to that,” Allen assured him.

|  | The next morning, Allen Ginsberg came by with a check and another harmonium. Up in Prabhupāda’s apartment, he demonstrated his melody for chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa, and then he and Prabhupāda talked.

|  | Allen: I was a little shy with him because I didn’t know where he was coming from. I had that harmonium I wanted to donate, and I had a little money. I thought it was great now that he was here to expound on the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra – that would sort of justify my singing. I knew what I was doing, but I didn’t have any theological background to satisfy further inquiries, and here was someone who did. So I thought that was absolutely great. Now I could go around singing Hare Kṛṣṇa, and if anybody wanted to know what it was, I could just send them to Svāmī Bhaktivedanta to find out. If anyone wanted to know the technical intricacies and the ultimate history, I could send them to him.

|  | He explained to me about his own teacher and about Caitanya and the lineage going back. His head was filled with so many things and what he was doing. He was already working on his translations. He always seemed to be sitting there just day after day and night after night. And I think he had one or two people helping him.

|  | Prabhupāda was very cordial with Allen. Quoting a passage from Bhagavad-gītā where Kṛṣṇa says that whatever a great man does, others will follow, he requested Allen to continue chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa at every opportunity, so that others would follow his example. He told about Lord Caitanya’s organizing the first civil disobedience movement in India, leading a saṅkīrtana protest march against the Muslim ruler. Allen was fascinated. He enjoyed talking with the Svāmī.

|  | But they had their differences. When Allen expressed his admiration for a well-known Bengali holy man, Prabhupāda said that the holy man was bogus. Allen was shocked. He’d never before heard a swami severely criticize another’s practice. Prabhupāda explained, on the basis of Vedic evidence, the reasoning behind his criticism, and Allen admitted that he had naively thought that all holy men were one-hundred-percent holy. But now he decided that he should not simply accept a sādhu, including Prabhupāda, on blind faith. He decided to see Prabhupāda in a more severe, critical light.

|  | Allen: I had a very superstitious attitude of respect, which probably was an idiot sense of mentality, and so Svāmī Bhaktivedanta’s teaching was very good to make me question that. It also made me question him and not take him for granted.

|  | Allen described a divine vision he’d had in which William Blake had appeared to him in sound, and in which he had understood the oneness of all things. A sādhu in Vṛndāvana had told Allen that this meant that William Blake was his guru. But to Prabhupāda this made no sense.

|  | Allen: The main thing, above and beyond all our differences, was an aroma of sweetness that he had, a personal, selfless sweetness like total devotion. And that was what always conquered me, whatever intellectual questions or doubts I had, or even cynical views of ego. In his presence there was a kind of personal charm, coming from dedication, that conquered all our conflicts. Even though I didn’t agree with him, I always liked to be with him.

|  | Allen agreed, at Prabhupāda’s request, to chant more and to try to give up smoking.

|  | ““Do you really intend to make these American boys into Vaiṣṇavas?” Allen asked.

“Yes,” Prabhupāda replied happily, “and I will make them all brāhmaṇas.”

|  | Allen left a $200 check to help cover the legal expenses for extending the Svāmī’s visa and wished him good luck. “Brāhmaṇas!” Allen didn’t see how such a transformation could be possible.

|  | September 23

|  | It was Rādhāṣṭamī, the appearance day of Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī, Lord Kṛṣṇa’s eternal consort. Prabhupāda held his second initiation. Keith became Kīrtanānanda, Steve became Satsvarūpa, Bruce became Brahmānanda, and Chuck became Acyutānanda. It was another festive day with a fire sacrifice in Prabhupāda’s front room and a big feast.

|  | Prabhupāda lived amid the drug culture, in a neighborhood where the young people were almost desperately attempting to alter their consciousness, whether by drugs or by some other means – whatever was available. Prabhupāda assured them that they could easily achieve the higher consciousness they desired by chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa. It was inevitable that in explaining Kṛṣṇa consciousness he would make allusions to the drug experience, even if only to show that the two were contrary paths. He was familiar already with Indian “sādhus” who took gāñjā and hashish on the plea of aiding their meditations. And even before he had left India, hippie tourists had become a familiar sight on the streets of Delhi.

|  | The hippies liked India because of the cultural mystique and easy access to drugs. They would meet their Indian counterparts, who assured them that taking hashish was spiritual, and then they would return to America and perpetrate their misconceptions of Indian spiritual culture.

|  | It was the way of life. The local head shops carried a full line of paraphernalia. Marijuana, LSD, peyote, cocaine, and hard drugs like heroin and barbiturates were easily purchased on the streets and in the parks. Underground newspapers reported important news on the drug scene, featured a cartoon character named Captain High, and ran crossword puzzles that only a seasoned “head” could answer.

|  | Prabhupāda had to teach that Kṛṣṇa consciousness was beyond the revered LSD trip. “Do you think taking LSD can produce ecstasy and higher consciousness?” he once asked his storefront audience. “Then just imagine a roomful of LSD. Kṛṣṇa consciousness is like that.” People would regularly come in and ask Svāmīji’s disciples, “Do you get high from this?” And the devotees would answer, “Oh, yes. You can get high just by chanting. Why don’t you try it?”

|  | Greg Scharf (Brahmānanda’s brother) hadn’t tried LSD; but he wanted higher consciousness, so he decided to try the chanting.

|  | Greg: I was eighteen. Everyone at the storefront had taken LSD, and I thought maybe I should too, because I wanted to feel like part of the crowd. So I asked Umāpati, “Hey, Umāpati, do you think I should try LSD? Because I don’t know what you guys are talking about.” He said no, that Svāmīji said you didn’t need LSD. I never did take it, so I guess it was OK.

|  | “Hayagrīva: Have you ever heard of LSD? It’s a psychedelic drug that comes like a pill, and if you take it you can get religious ecstasies. Do you think this can help my spiritual life?

Prabhupāda: You don’t need to take anything for your spiritual life. Your spiritual life is already here.“

|  | Had anyone else said such a thing, Hayagrīva would never have agreed with him. But because Svāmīji seemed “so absolutely positive,” therefore “there was no question of not agreeing.”

|  | Satsvarūpa: I knew Svāmīji was in a state of exalted consciousness, and I was hoping that somehow he could teach the process to me. In the privacy of his room, I asked him, “Is there spiritual advancement that you can make from which you won’t fall back?” By his answer – “Yes” – I was convinced that my own attempts to be spiritual on LSD, only to fall down later, could be replaced by a total spiritual life such as Svāmīji had. I could see he was convinced, and then I was convinced.

|  | Greg: LSD was like the spiritual drug of the times, and Svāmīji was the only one who dared to speak out against it, saying it was nonsense. I think that was the first battle he had to conquer in trying to promote his movement on the Lower East Side. Even those who came regularly to the storefront thought that LSD was good.

|  | Probably the most famous experiments with LSD in those days were by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, Harvard psychology instructors who studied the effects of the drug, published their findings in professional journals, and advocated the use of LSD for self-realization and fulfillment. After being fired from Harvard, Timothy Leary went on to become a national priest of LSD and for some time ran an LSD commune in Millbrook, New York.

|  | When the members of the Millbrook commune heard about the swami on the Lower East Side who led his followers in a chant that got you high, they began visiting the storefront. One night, a group of about ten hippies from Millbrook came to Svāmīji’s kīrtana. They all chanted (not so much in worship of Kṛṣṇa as to see what kind of high the chanting could produce), and after the lecture a Millbrook leader asked about drugs. Prabhupāda replied that drugs were not necessary for spiritual life, that they could not produce spiritual consciousness, and that all drug-induced religious visions were simply hallucinations. To realize God was not so easy or cheap that one could do it just by taking a pill or smoking. Chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa, he explained, was a purifying process to uncover one’s pure consciousness. Taking drugs would increase the covering and bar one from self-realization.

|  | “'But have you ever taken LSD?' The question now became a challenge.

'No,' Prabhupāda replied. 'I have never taken any of these things, not even cigarettes or tea.'“

|  | “If you haven’t taken it, then how can you say what it is?” The Millbrookers looked around, smiling. Two or three even burst out with laughter, and they snapped their fingers, thinking the Svāmī had been checkmated.

|  | “I have not taken,” Prabhupāda replied regally from his dais. “But my disciples have taken all these things – marijuana, LSD – many times, and they have given them all up. You can hear from them. Hayagrīva, you can speak.” And Hayagrīva sat up a little and spoke out in his stentorian best.

|  | “Well, no matter how high you go on LSD, you eventually reach a peak, and then you have to come back down. Just like traveling into outer space in a rocket ship. [He gave one of Svāmīji’s familiar examples.] Your spacecraft can travel very far away from the earth for thousands of miles, day after day, but it cannot simply go on traveling and traveling. Eventually it must land. On LSD, we experience going up, but we always have to come down again. That’s not spiritual consciousness. When you actually attain spiritual or Kṛṣṇa consciousness, you stay high. Because you go to Kṛṣṇa, you don’t have to come down. You can stay high forever.“

|  | Prabhupāda was sitting in his back room with Hayagrīva and Umāpati and other disciples. The evening meeting had just ended, and the visitors from Millbrook had gone. “Kṛṣṇa consciousness is so nice, Svāmīji,” Umāpati spoke up. “You just get higher and higher, and you don’t come down.”

|  | Prabhupāda smiled. “Yes, that’s right.”

|  | “No more coming down,” Umāpati said, laughing, and the others also began to laugh. Some clapped their hands, repeating, “No more coming down.”

|  | The conversation inspired Hayagrīva and Umāpati to produce a new handbill:

|  | “STAY HIGH FOREVER!

No More Coming Down

Practice Kṛṣṇa Consciousness

Expand your Consciousness by practicing the

* TRANSCENDENTAL SOUND VIBRATION *

HARE KRISHNA HARE KRISHNA KRISHNA KRISHNA HARE HARE

HARE RAMA HARE RAMA RAMA RAMA HARE HARE“

|  | The leaflet went on to extol Kṛṣṇa consciousness over any other high. It included phrases like “end all bringdowns” and “turn on,” and it spoke against “employing artificially induced methods of self-realization and expanded consciousness.” Someone objected to the flyer’s “playing too much off the hippie mentality,” but Prabhupāda said it was all right.

|  | Greg: When these drug people on the Lower East Side came and talked to Svāmīji, he was so patient with them. He was speaking on a philosophy which they had never heard before. When someone takes LSD, they’re really into themselves, and they don’t hear properly when someone talks to them. So Svāmīji would make particular points, and they wouldn’t understand him. So he would have to make the same point again. He was very patient with these people, but he would not give in to their claim that LSD was a bona fide spiritual aid to self-realization.

|  | October 1966

|  | Tompkins Square Park was the park on the Lower East Side. On the south, it was bordered by Seventh Street, with its four- and five-storied brownstone tenements. On the north side was Tenth, with more brownstones, but in better condition, and the very old, small building that housed the Tompkins Square branch of the New York Public Library. On Avenue B, the park’s east border, stood St. Brigid’s Church, built in 1848, when the neighborhood had been entirely Irish. The church, school, and rectory still occupied much of the block. And the west border of the park, Avenue A, was lined with tiny old candy stores selling newspapers, magazines, cigarettes, and egg-creme sodas at the counter. There were also a few bars, several grocery stores, and a couple of Slavic restaurants specializing in inexpensive vegetable broths, which brought Ukranians and hippies side by side for bodily nourishment.

|  | The park’s ten acres held many tall trees, but at least half the park was paved. A network of five-foot-high heavy wrought-iron fences weaved through the park, lining the walkways and protecting the grass. The fences and the many walkways and entrances to the park gave it the effect of a maze.

|  | Since the weather was still warm and it was Sunday, the park was crowded with people. Almost all the space on the benches that lined the walkways was occupied. There were old people, mostly Ukranians, dressed in outdated suits and sweaters, even in the warm weather, sitting together in clans, talking. There were many children in the park also, mostly Puerto Ricans and blacks but also fair-haired, hard-faced slum kids racing around on bikes or playing with balls and Frisbees. The basketball and handball courts were mostly taken by the teenagers. And as always, there were plenty of loose, running dogs.

|  | A marble miniature gazebo (four pillars and a roof, with a drinking fountain inside) was a remnant from the old days – 1891, according to the inscription. On its four sides were the words HOPE, FAITH, CHARITY, and TEMPERANCE. But someone had sprayed the whole structure with black paint, making crude designs and illegible names and initials. Today, a bench had been taken over by several conga and bongo drummers, and the whole park pulsed with their demanding rhythms.

|  | And the hippies were there, different from the others. The bearded Bohemian men and their long-haired young girlfriends dressed in old blue jeans were still an unusual sight. Even in the Lower East Side melting pot, their presence created tension. They were from middle-class families, and so they had not been driven to the slums by dire economic necessity. This created conflicts in their dealings with the underprivileged immigrants. And the hippies’ well-known proclivity for psychedelic drugs, their revolt against their families and affluence, and their absorption in the avant-garde sometimes made them the jeered minority among their neighbors. But the hippies just wanted to do their own thing and create their own revolution for “love and peace,” so usually they were tolerated, although not appreciated.

|  | There were various groups among the young and hip at Tompkins Square Park. There were friends who had gone to the same school together, who took the same drug together, or who agreed on a particular philosophy of art, literature, politics, or metaphysics. There were lovers. There were groups hanging out together for reasons undecipherable, except for the common purpose of doing their own thing. And there were others, who lived like hermits – a loner would sit on a park bench, analyzing the effects of cocaine, looking up at the strangely rustling green leaves of the trees and the blue sky above the tenements and then down to the garbage at his feet, as he helplessly followed his mind from fear to illumination, to disgust to hallucination, on and on, until after a few hours the drug began to wear off and he was again a common stranger. Sometimes they would sit up all night, “spaced out” in the park, until at last, in the light of morning, they would stretch out on benches to sleep.

|  | Hippies especially took to the park on Sundays. They at least passed through the park on their way to St. Mark’s Place, Greenwich Village, or the Lexington Avenue subway at Astor Place, or the IND subway at Houston and Second, or to catch an uptown bus on First Avenue, a downtown bus on Second, or a crosstown on Ninth. Or they went to the park just to get out of their apartments and sit together in the open air – to get high again, to talk, or to walk through the park’s maze of pathways.

|  | But whatever the hippies’ diverse interests and drives, the Lower East Side was an essential part of the mystique. It was not just a dirty slum; it was the best place in the world to conduct the experiment in consciousness. For all its filth and threat of violence and the confined life of its brownstone tenements, the Lower East Side was still the forefront of the revolution in mind expansion. Unless you were living there and taking psychedelics or marijuana, or at least intellectually pursuing the quest for free personal religion, you weren’t enlightened, and you weren’t taking part in the most progressive evolution of human consciousness. And it was this searching – a quest beyond the humdrum existence of the ordinary, materialistic, “straight” American – that brought unity to the otherwise eclectic gathering of hippies on the Lower East Side.

|  | Into this chaotic pageant Svāmīji entered with his followers and sat down to hold a kīrtana. Three or four devotees who arrived ahead of him selected an open area of the park, put out the Oriental carpet Robert Nelson had donated, sat down on it, and began playing karatālas and chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa. Immediately some boys rode up on their bicycles, braked just short of the carpet, and stood astride their bikes, curiously and irreverently staring. Other passersby gathered to listen.

|  | Meanwhile Svāmīji, accompanied by half a dozen disciples, was walking the eight blocks from the storefront. Brahmānanda carried the harmonium and the Svāmī’s drum. Kīrtanānanda, who was now shaven-headed at Svāmīji’s request and dressed in loose-flowing canary yellow robes, created an extra sensation. Drivers pulled their cars over to have a look, their passengers leaning forward, agape at the outrageous dress and shaved head. As the group passed a store, people inside would poke each other and indicate the spectacle. People came to the windows of their tenements, taking in the Svāmī and his group as if a parade were passing. The Puerto Rican tough guys, especially, couldn’t restrain themselves from exaggerated reactions. “Hey, Buddha!” they taunted. “Hey, you forgot to change your pajamas!” They made shrill screams as if imitating Indian war whoops they had heard in Hollywood westerns.

|  | “Hey, A-rabs!” exclaimed one heckler, who began imitating what he thought was an Eastern dance. No one on the street knew anything about Kṛṣṇa consciousness, nor even of Hindu culture and customs. To them, the Svāmī’s entourage was just a bunch of crazy hippies showing off. But they didn’t quite know what to make of the Svāmī. He was different. Nevertheless, they were suspicious. Some, however, like Irving Halpern, a veteran Lower East Side resident, felt sympathetic toward this stranger, who was “apparently a very dignified person on a peaceful mission.”

|  | Irving Halpern: A lot of people had spectacularized notions of what a swami was. As though they were going to suddenly see people lying on little mattresses made out of nails – and all kinds of other absurd notions. Yet here came just a very graceful, peaceful, gentle, obviously well-meaning being into a lot of hostility.

|  | “Hippies!”

“What are they, Communists?”

|  | While the young taunted, the middle-aged and elderly shook their heads or stared, cold and uncomprehending. The way to the park was spotted with blasphemies, ribald jokes, and tension, but no violence. After the successful kīrtana in Washington Square Park, Prabhupāda had regularly been sending out “parades” of three or four devotees, chanting and playing hand cymbals through the streets and sidewalks of the Lower East Side. On one occasion, they had been bombarded with water balloons and eggs, and they were sometimes faced with bullies looking for a fight. But they were never attacked – just stared at, laughed at, or shouted after.

|  | Today, the ethnic neighbors just assumed that Prabhupāda and his followers had come onto the streets dressed in outlandish costumes as a joke, just to turn everything topsy-turvy and cause stares and howls. They felt that their responses were only natural for any normal, respectable American slum-dweller.

|  | So it was quite an adventure before the group even reached the park. Svāmīji, however, remained unaffected. “What are they saying?” he asked once or twice, and Brahmānanda explained. Prabhupāda had a way of holding his head high, his chin up, as he walked forward. It made him look aristocratic and determined. His vision was spiritual – he saw everyone as a spiritual soul and Kṛṣṇa as the controller of everything. Yet aside from that, even from a worldly point of view he was unafraid of the city’s pandemonium. After all, he was an experienced “Calcutta man.”

|  | The kīrtana had been going for about ten minutes when Svāmīji arrived. Stepping out of his white rubber slippers, just as if he were home in the temple, he sat down on the rug with his followers, who had now stopped their singing and were watching him. He wore a pink sweater, and around his shoulders a khādī wrapper. He smiled. Looking at his group, he indicated the rhythm by counting, one … two … three. Then he began clapping his hands heavily as he continued counting, “One … two … three.” The karatālas followed, at first with wrong beats, but he kept the rhythm by clapping his hands, and then they got it, clapping hands, clashing cymbals artlessly to a slow, steady beat.

|  | He began singing prayers that no one else knew. Vande ’haṁ śrī-guroḥ śrī-yuta-pada-kamalaṁ śrī-gurūn vaiṣṇavāṁś ca. His voice was sweet like the harmonium, rich in the nuances of Bengali melody. Sitting on the rug under a large oak tree, he sang the mysterious Sanskrit prayers. None of his followers knew any mantra but Hare Kṛṣṇa, but they knew Svāmīji. And they kept the rhythm, listening closely to him while the trucks rumbled on the street and the conga drums pulsed in the distance.

|  | As he sang – śrī-rūpaṁ sāgrajātaṁ – the dogs came by, kids stared, a few mockers pointed fingers: “Hey, who is that priest, man?” But his voice was a shelter beyond the clashing dualities. His boys went on ringing cymbals while he sang alone: śrī-rādhā-kṛṣṇa-pādān.

|  | Prabhupāda sang prayers in praise of Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī’s pure conjugal love for Kṛṣṇa, the beloved of the gopīs. Each word, passed down for hundreds of years by the intimate associates of Kṛṣṇa, was saturated with deep transcendental meaning that only he understood. Saha-gaṇa-lalitā-śrī-viśākhānvitāṁś ca. They waited for him to begin Hare Kṛṣṇa, although hearing him chant was exciting enough.

|  | More people came – which was what Prabhupāda wanted. He wanted them chanting and dancing with him, and now his followers wanted that too. They wanted to be with him. They had tried together at the U.N., Ananda Ashram, and Washington Square. It seemed that this would be the thing they would always do – go with Svāmīji and sit and chant. He would always be with them, chanting.

|  | Then he began the mantra – Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare. They responded, too low and muddled at first, but he returned it to them again, singing it right and triumphant. Again they responded, gaining heart, ringing karatālas and clapping hands – one … two … three, one … two … three. Again he sang it alone, and they stayed, hanging closely on each word, clapping, beating cymbals, and watching him looking back at them from his inner concentration – his old-age wisdom, his bhakti – and out of love for Svāmīji, they broke loose from their surroundings and joined him as a chanting congregation. Svāmīji played his small drum, holding its strap in his left hand, bracing the drum against his body, and with his right hand playing intricate mṛdaṅga rhythms.

|  | Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare. He was going strong after half an hour, repeating the mantra, carrying them with him as interested onlookers gathered in greater numbers. A few hippies sat down on the edge of the rug, copying the cross-legged sitting posture, listening, clapping, trying the chanting, and the small inner circle of Prabhupāda and his followers grew, as gradually more people joined.

|  | As always, his kīrtana attracted musicians.

|  | Irving Halpern: I make flutes, and I play musical instruments. There are all kinds of different instruments that I make. When the Svāmī came, I went up and started playing, and he welcomed me. Whenever a new musician would join and play their first note, he would extend his arms. It would be as though he had stepped up to the podium and was going to lead the New York Philharmonic. I mean, there was this gesture that every musician knows. You just know when someone else wants you to play with them and feels good that you are playing with them. And this very basic kind of musician communication was there with him, and I related to it very quickly. And I was happy about it.

|  | Lone musicians were always loitering in different parts of the park, and when they heard they could play with the Svāmī’s chanting and that they were welcome, then they began to come by, one by one. A saxophone player came just because there was such a strong rhythm section to play with. Others, like Irving Halpern, saw it as something spiritual, with good vibrations. As the musicians joined, more passersby were drawn into the kīrtana. Prabhupāda had been singing both lead and chorus, and many who had joined now sang the lead part also, so that there was a constant chorus of chanting. During the afternoon, the crowd grew to more than a hundred, with a dozen musicians trying – with their conga and bongo drums, bamboo flutes, metal flutes, mouth organs, wood and metal “clackers,” tambourines, and guitars – to stay with the Svāmī.

|  | Irving Halpern: The park resounded. The musicians were very careful in listening to the mantras. When the Svāmī sang Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare/ Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare, there was sometimes a Kṛ-ṣa-ṇa, a tripling of what had been a double syllable. It would be usually on the first stanza, and the musicians really picked up on it. The Svāmī would pronounce it in a particular way, and the musicians were really meticulous and listened very carefully to the way the Svāmī would sing. And we began to notice that there were different melodies for the same brief sentence, and we got to count on that one regularity, like one would count on the conductor of an orchestra or the lead singer of a madrigal. It was really pleasant, and people would dig one another in their ribs. They would say, “Hey, see!” We would catch and repeat a particular subtle pronunciation of a Sanskrit phrase that the audience, in their enthusiasm, while they would be dancing or playing, had perhaps missed. Or the Svāmī would add an extra beat, but it meant something, in the way in which the drummer, who at that time was the Svāmī, the main drummer, would hit the drums.

|  | I have talked to a couple of musicians about it, and we agreed that in his head this Svāmī must have had hundreds and hundreds of melodies that had been brought back from the real learning from the other side of the world. So many people came there just to tune in to the musical gift, the transmission of the dharma. “Hey,” they would say, “listen to this holy monk.” People were really sure there were going to be unusual feats, grandstanding, flashy levitation, or whatever people expected was going to happen. But when the simplicity of what the Svāmī was really saying, when you began to sense it – whether you were motivated to actually make a lifetime commitment and go this way of life, or whether you merely wanted to appreciate it and place it in a place and give certain due respect to it – it turned you around.

|  | And that was interesting, too, the different ways in which people regarded the kīrtana. Some people thought it was a prelude. Some people thought it was a main event. Some people liked the music. Some people liked the poetic sound of it.

|  | Then Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky arrived, along with some of their friends. Allen surveyed the scene and found a seat among the chanters. With his black beard, his eyeglasses, his bald spot surrounded by long, black ringlets of hair, Allen Ginsberg, the poet-patriarch come to join the chanting, greatly enhanced the local prestige of the kīrtana. Prabhupāda, while continuing his ecstatic chanting and drum-playing, acknowledged Allen and smiled.

|  | A reporter from The New York Times dropped by and asked Allen for an interview, but he refused: “A man should not be disturbed while worshiping.” The Times would have to wait.

|  | Allen: Tompkins Square Park was a hotbed of spiritual conflict in those days, so it was absolutely great. All of a sudden, in the midst of all the talk and drugs and theory, for some people to put their bodies, their singing, to break through the intellectual ice and come out with total bhakti – that was really amazing.

|  | The blacks and Puerto Ricans were out there with drums too, doing conga. But here was a totally different kind of group, some of them with shaven heads, and it was interesting. It was a repetitious chant, but that was also great. It was an easy chant to get into. It was an open scene. There was no boxed corner there in the actual practice. So, general smiles and approval and encouragement as a beginning of some kind of real communal get-together in the park, with a kind of serious underbase for exchange – instead of just hog-dog on the drums.

|  | Prabhupāda was striking to see. His brow was furrowed in the effort of singing loud, and his visage was strong. The veins in his temples stood out visibly, and his jaw jutted forward as he sang his “Hare Kṛṣṇa! Hare Kṛṣṇa!” for all to hear. Although his demeanor was pleasant, his chanting was intensive, sometimes straining, and everything about him was concentration.

|  | It wasn’t someone else’s yoga retreat or silent peace vigil, but a pure chanting be-in of Prabhupāda’s own doing. It was a new wave, something everyone could take part in. The community seemed to be accepting it. It became so popular that the ice cream vendor came over to make sales. Beside Prabhupāda a group of young, blond-haired boys, five or six years old, were just sitting around. A young Polish boy stood staring. Someone began burning frankincense on a glowing coal in a metal strainer, and the sweet fumes billowed among the flutists, drummers, and chanters.

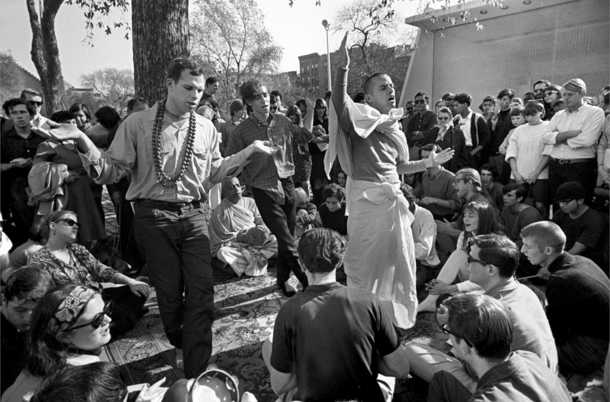

|  | Svāmīji motioned to his disciples, and they got up and began dancing. Tall, thin Stryadhīśa, his back pockets stuffed with Stay High Forever flyers, raised his hands and began to dance. Beside him, in a black turtleneck, big chanting beads around his neck, danced Acyutānanda, his curly, almost frizzy, hair long and disarrayed. Then Brahmānanda got up. He and Acyutānanda stood facing each other, arms outstretched as in the picture of Lord Caitanya’s kīrtana. Photographers in the crowd moved forward. The boys danced, shifting their weight from left foot to right foot, striking a series of angelic poses, their large, red chanting beads around their necks. They were doing the Svāmī step.

|  |  Brahmānanda: Once I got up, I thought I would have to remain standing for as long as Svāmīji played the drum. It will be an offense, I thought, if I sit down while he’s still playing. So I danced for an hour.

Brahmānanda: Once I got up, I thought I would have to remain standing for as long as Svāmīji played the drum. It will be an offense, I thought, if I sit down while he’s still playing. So I danced for an hour.

|  | Prabhupāda gave a gesture of acceptance by a typically Indian movement of his head, and then he raised his arms, inviting more dancers. More of his disciples began dancing, and even a few hippies got up and tried it. Prabhupāda wanted everyone to sing and dance in saṅkīrtana. The dance was a sedate swaying and a stepping of bare feet on the rug, and the dancers’ arms were raised high, their fingers extended toward the sky above the branches of the autumn trees. Here and there throughout the crowd, chanters were enjoying private ecstasies: a girl with her eyes closed played finger cymbals and shook her head dreamily as she chanted. A Polish lady with a very old, worn face and a babushka around her head stared incredulously at the girl. Little groups of old women in kerchiefs, some of them wearing sunglasses, stood here and there among the crowd, talking animatedly and pointing out the interesting sights in the kīrtana. Kīrtanānanda was the only one in a dhotī, looking like a young version of Prabhupāda. The autumn afternoon sunlight fell softly on the group, spotlighting them in a golden glow with long, cool shadows.

|  | The harmonium played a constant drone, and a boy wearing a military fatigue jacket improvised atonal creations on a wooden recorder. Yet the total sound of the instruments blended, and Svāmīji’s voice emerged above the mulling tones of each chord. And so it went for hours. Prabhupāda held his head and shoulders erect, although at the end of each line of the mantra, he would sometimes shrug his shoulders before he started the next line. His disciples stayed close by him, sitting on the same rug, religious ecstasy visible in their eyes. Finally, he stopped.

|  | Immediately he stood up, and they knew he was going to speak. It was four o’clock, and the warm autumn sun was still shining on the park. The atmosphere was peaceful and the audience attentive and mellow from the concentration on the mantra. He began to speak to them, thanking everyone for joining in the kīrtana. The chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa, he said, had been introduced five hundred years ago in West Bengal by Caitanya Mahāprabhu. Hare means “O energy of the Lord,” Kṛṣṇa is the Lord, and Rāma is also a name of the Supreme Lord, meaning “the highest pleasure.” His disciples sat at his feet, listening. Rāya Rāma squinted through his shielding hand into the sun to see Svāmīji, and Kīrtanānanda’s head was cocked to one side, like a bird’s who is listening to the ground.

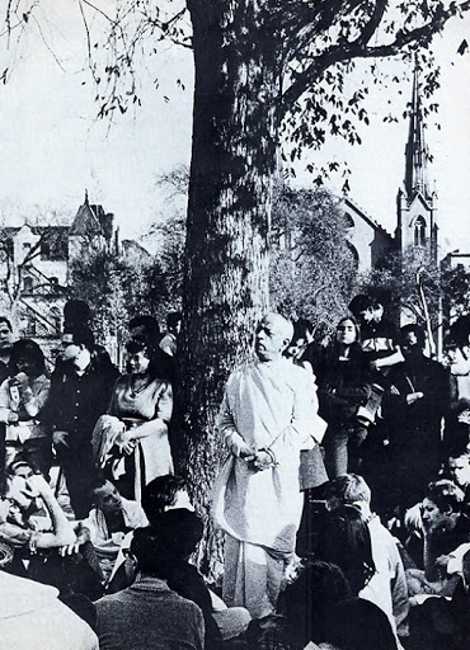

|  |  He stood erect by the stout oak, his hands folded loosely before him in a proper speaker’s posture, his light saffron robes covering him gracefully. The tree behind him seemed perfectly placed, and the sunshine dappled leafy shadows against the thick trunk. Behind him, through the grove of trees, was the steeple of St. Brigid’s. On his right was a dumpy, middle-aged woman wearing a dress and hairdo that had been out of style in the United States for twenty-five years. On his left was a bold looking hippie girl in tight denims and beside her a young black man in a black sweater, his arms folded across his chest. Next was a young father holding an infant, then a bearded young street sādhu, his long hair parted in the middle, and two ordinary, short-haired middle-class men and their young female companions. Many in the crowd, although standing close by, became distracted, looking off here and there.

He stood erect by the stout oak, his hands folded loosely before him in a proper speaker’s posture, his light saffron robes covering him gracefully. The tree behind him seemed perfectly placed, and the sunshine dappled leafy shadows against the thick trunk. Behind him, through the grove of trees, was the steeple of St. Brigid’s. On his right was a dumpy, middle-aged woman wearing a dress and hairdo that had been out of style in the United States for twenty-five years. On his left was a bold looking hippie girl in tight denims and beside her a young black man in a black sweater, his arms folded across his chest. Next was a young father holding an infant, then a bearded young street sādhu, his long hair parted in the middle, and two ordinary, short-haired middle-class men and their young female companions. Many in the crowd, although standing close by, became distracted, looking off here and there.

|  | Prabhupāda explained that there are three platforms – sensual, mental, and intellectual – and above them is the spiritual platform. The chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa is on the spiritual platform, and it is the best process for reviving our eternal, blissful consciousness. He invited everyone to attend the meetings at 26 Second Avenue and concluded his brief speech by saying, “Thank you very much. Please chant with us.” Then he sat down, took the drum, and began the kīrtana again.

|  | If it were risky for a seventy-one-year-old man to thump a drum and shout so loud, then he would take that risk for Kṛṣṇa. It was too good to stop. He had come far from Vṛndāvana, survived the non-Kṛṣṇa yoga society, waited all winter in obscurity. America had waited hundreds of years with no Kṛṣṇa-chanting. No “Hare Kṛṣṇa” had come from Thoreau’s or Emerson’s appreciations, though they had pored over English translations of the Gītā and Purāṇas. And no kīrtana had come from Vivekananda’s famous speech on behalf of Hinduism at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. So now that he finally had kṛṣṇa-bhakti going, flowing like the Ganges to the sea, it could not stop. In his heart he felt the infinite will of Lord Caitanya to deliver the fallen souls.

|  | He knew this was the desire of Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu and his own spiritual master, even though caste-conscious brāhmaṇas in India would disapprove of his associating with such untouchables as these drug-mad American meat-eaters and their girlfriends. But Svāmīji explained that he was in full accord with the scriptures. The Bhāgavatam had clearly stated that Kṛṣṇa consciousness should be delivered to all races. Everyone was a spiritual soul, and regardless of birth they could be brought to the highest spiritual platform by chanting the holy name. Never mind whatever sinful things they were doing, these people were perfect candidates for Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Tompkins Square Park was Kṛṣṇa’s plan; it was also part of the earth, and these people were members of the human race. And the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa was the dharma of the age.

|  | Walking back home in the early evening, past the shops and crowded tenements, followed by more than a dozen interested new people from the park, the Svāmī again sustained occasional shouts and taunts. But those who followed him from the park were still feeling the aura of an ecstasy that easily tolerated a few taunts from the street. Prabhupāda, especially, was undisturbed. As he walked with his head high, not speaking, he was gravely absorbed in his thoughts. And yet his eyes actively noticed people and places and exchanged glances with those whom he passed on his way along Seventh Street, past the churches and funeral homes, across First Avenue to the noisy, heavily trafficked Second Avenue, then down Second past liquor stores, coin laundries, delicatessens, past the Iglesia Alianza Cristiana Missionera, the Koh-I-Noor Intercontinental Restaurant Palace, then past the Church of the Nativity, and finally back home to number twenty-six.

|  | There was a crowd of people from the park standing on the sidewalk outside the storefront – young people waiting for him to arrive and unlock the door to Matchless Gifts. They wanted to know more about the dance and the chant and the elderly swami and his disciples who had created such a beautiful scene in the park. They filled the storefront. Outside on the sidewalk, the timid or uncommitted loitered near the door or window, smoking and waiting or peering in and trying to see the paintings on the wall. Svāmīji entered and walked directly to his dais and sat down before the largest gathering that had ever graced his temple. He spoke further of Kṛṣṇa consciousness, the words coming as naturally as breathing as he quoted the Sanskrit authority behind what they had all been experiencing in the park. Just as they had all chanted today, he said, so everyone should chant always.

|  | A long-haired girl sitting close to Svāmīji’s dais raised her hand and asked, seemingly in trance, “When I am chanting, I feel a great concentration of energy on my forehead, and then a buzzing comes and a reddish light.”

|  | “Just keep on chanting,” Svāmīji replied. “It will clear up.”

“Well, what does the chanting produce?” She seemed to be coming out of her trance now.

|  | A man spoke up without raising his hand. “But isn’t it just a kind of hypnotism on sound? Like if I chanted Coca-Cola over and over, wouldn’t it be the same?”

|  | “No,” Prabhupāda replied, “you take any word, repeat it for ten minutes, and you will feel disgusted. But we chant twenty-four hours, and we don’t feel tired. Oh, we feel new energy.” The questions seemed more relevant today. The guests had all been chanting in the park, and now they were probing philosophically into what they had experienced. The Svāmī’s followers marked this as a victory. And they felt some responsibility as hosts and guides for the others. Svāmīji had asked Kīrtanānanda to prepare some prasādam for the guests, and soon Kīrtanānanda appeared with small paper cups of sweet rice for everyone.

|  | “The chanting process is just to cleanse the mind,” said Prabhupāda. “We have so many misunderstandings about ourself, about this world, about God, and about the relationships between these things. We have so many misgivings. This chanting will help to cleanse the mind. Then you will understand that this chanting is not different from Kṛṣṇa.”

|  | A boy who was accompanying the long-haired girl spoke out incoherently: “Yes. No. I... I... I...”

|  | Prabhupāda: Yes. Yes. Yes. In the beginning we have to chant. We may be in whatever position we are. It doesn’t matter. If you begin chanting, the first benefit will be ceto-darpaṇa-mārjanam: the mind will be clear of all dirty things, and the next stage will be that the sufferings, the miseries of this material world, will subside.

|  | Boy: Well, I don’t quite understand what the material world is, because …

|  | Prabhupāda: The material world is full of sufferings and miseries. Don’t you understand that? Are you happy?

|  | Boy: Sometimes I’m happy, sometimes I’m not.

|  | Prabhupāda: No. You are not happy. That “sometimes” is your imagination. Just like a diseased man says, “Oh, yes, I am well.” What is that “well”? He is going to die, and he is well?

|  | Boy: I don’t claim any ultimate happiness.

|  | Prabhupāda: No, you do not know what happiness is.

|  | Boy: But it’s greater or lesser.

|  | Prabhupāda: Yes, you do not know what is happiness.

|  | An older man, standing with his arms folded near the rear of the temple: Well, of course, that sorrow or that suffering might add the spice to make that suffering that goes in between seem happiness.

|  | Prabhupāda: No. The thing is that there are different kinds of miseries. That we all understand. It is only due to our ignorance that we don’t care for it. Just like a man who is suffering for a long time. He has forgotten what is real happiness. Similarly, the sufferings are there already. For example (and he directed himself to the young man with his girlfriend), take for example that you are a young man. Now would you like to become an old man?

|  | Boy: I will become an old man in the process of –

|  | Prabhupāda: “You will become” means you will be forced to become an old man. But you don’t like to become an old man.

|  | Prabhupāda: Yes. Yes. Forced! You will be forced.

|  | Boy: I don’t see why.

|  | Prabhupāda: If you don’t want to become an old man, you will be forced to become an old man.

|  | Boy: It’s one of the conditions of –

|  | Prabhupāda: Yes. That condition is miserable.

|  | Boy: I find it not miserable.

|  | Prabhupāda: Because you’re a young man. But ask any old man how he is suffering. You see? A diseased man – do you want to be diseased?

|  | Boy: I wouldn’t search it out.

|  | Prabhupāda: Hmm?

|  | Boy: I wouldn’t search it out.

|  | Prabhupāda: No, no. Just answer me. Do you like to be diseased?

|  | Boy: What is disease?

|  | Prabhupāda: Just answer.

|  | Boy: What is disease?

|  | Prabhupāda: Oh? You have never suffered from disease? You have never suffered from disease? (Prabhupāda looks dramatically incredulous.)

|  | Boy: I have had … I have had the mumps and the measles and whooping cough, which is what everyone has – and you get over it. (Some people in the audience laugh.)

|  | Prabhupāda: Everyone may be suffering, but that does not mean that it is not suffering. We have to admit that we are always in suffering.

|  | Boy: If I have never known happiness, I feel sure I have never known suffering either.

|  | Prabhupāda: That is due to your ignorance. We are in suffering. We don’t want to die, but death is there. We don’t want to be diseased, but disease is there. We don’t want to become old – old age is there. We don’t want so many things, but they are forced upon us, and any sane man will admit that these are sufferings. But if you are accustomed to take these sufferings, then you say it is all right. But any sane man won’t like to be diseased. He won’t like to be old. And he won’t like to die. Why do you have this peace movement? Because if there is war, there will be death. So people are afraid. They are making agitation: “There should be no war.” Do you think that death is a very pleasurable thing?

|  | Boy: I have never experienced –

|  | Prabhupāda: You have experienced – and forgotten. Many times you have died. You have experienced, but you have forgotten. Forgetfulness is no excuse. Suppose a child forgot some suffering. That does not mean he did not suffer.

|  | Boy: No, I agree. I agree.

|  | Prabhupāda: Yes. So suffering is there. You have to take direction from realized souls, from authorities. Just like in the Bhagavad-gītā it is said, duḥkhālayam aśāśvatam: this world is full of miseries. So one has to realize it. Unless we understand that this place is miserable, there is no question of how to get out of it. A person who doesn’t develop this understanding is not fully developed. Just like the animals – they do not understand what misery is. They are satisfied.

|  | It was late when he finally returned to his apartment. One of the boys brought him a cup of hot milk, and someone remarked they should do the chanting in the park every week. “Every day,” he replied. Even while half a dozen people were present, he lay down on his thin mat. He continued to speak for some minutes, and then his voice trailed off, preaching in fragmented words. He appeared to doze. It was ten o’clock. They tiptoed out, softly shutting the door.

|  | October 10

|  | It was early. Svāmīji had not yet come down for class, and the sun had not yet risen. Satsvarūpa and Kīrtanānanda sat on the floor of the storefront, reading a clipping from the morning Times.

|  | Satsvarūpa: Has the Svāmī seen it?

|  | Kīrtanānanda: Yes, just a few minutes ago. He said it’s very important. It’s historic. He especially liked that it was The New York Times.

|  | Satsvarūpa (reading aloud): “SWAMI’S FLOCK CHANTS IN PARK TO FIND ECSTASY.”

|  | Fifty Followers Clap and Sway to Hypnotic Music at East Side Ceremony. Sitting under a tree in a Lower East Side park and occasionally dancing, fifty followers of a Hindu swami repeated a sixteen-word chant for two hours yesterday...

|  | It was more than two hours.

|  | ...for two hours yesterday afternoon to the accompaniment of cymbals, tambourines, sticks, drums, bells, and a small reed organ. Repetition of the chant, Svāmī A. C. Bhaktivedanta says, is the best way to achieve self-realization in this age of destruction. While children played on Hoving’s Hill, a pile of dirt in the middle of Tompkins Square Park...

|  | Hoving’s Hill?

|  | Kīrtanānanda: I think it’s a joke named after the Parks Commissioner.

|  | Satsvarūpa: Oh.

|  | ...Hoving’s Hill, a pile of dirt in the middle of Tompkins Square Park, or bicycled along the sunny walks, many in the crowd of about a hundred persons standing around the chanters found themselves swaying to or clapping hands in time to the hypnotic rhythmic music. “It brings a state of ecstasy,” said Allen Ginsberg the poet, who was one of the celebrants. “For one thing,” Allen Ginsberg said, “the syllables force yoga breath control. That’s one physiological explanation.

|  | Satsvarūpa and Kīrtanānanda (laughing): That’s nonsense.

|  | The ecstasy of the chant of mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa Hare Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare...

|  | Kīrtanānanda: The Svāmī said that’s the best part. Because they have printed the mantra, it’s all-perfect. Whoever reads this can be purified just the same as if they had chanted.

|  | Satsvarūpa (continuing): “...has replaced LSD and other drugs for many of the swami’s followers,” Mr. Ginsberg said. He explained that Hare Kṛṣṇa, pronounced Hahray, is the name for Vishnu, a Hindu god, as the “bringer of light.” Rama, pronounced Rahmah, is the incarnation of Vishnu as “the prince of responsibility.”

|  | What? Where did he get that? It sounds like something out of an encyclopedia.

|  | “The chant, therefore, names different aspects of God,” Mr. Ginsberg said.

|  | Why so much from Mr. Ginsberg? Why not Svāmīji?

|  | Another celebrant, 26-year-old Howard M. Wheeler, who described himself as a former English instructor at Ohio State University, now devoting his full time to the swami, said, “I myself took fifty doses of LSD and a dozen of peyote in two years, and now nothing.”

|  | (Laughter.)

|  | The swami orders his followers to give up “all intoxicants, including coffee, tea, and cigarettes,” he said in an interview after the ceremony. “In this sense we are helping your government,” he added. However, he indicated the government apparently has not appreciated this help sufficiently, for the Department of Immigration recently told Svāmī Bhaktivedanta that his one-year visitor’s visa had expired and that he must leave, he said. The case is being appealed.

|  | The swami, a swarthy man with short-cropped grayish hair and clad in a salmon-colored robe over a pink sweater, said that when he first met his own teacher, or guru, in 1922, he was told to spread the cult of Kṛṣṇa to the Western countries through the English language. “Therefore in this old age (71) I have taken so much risk.”

|  | It says that we’re going to come there and chant every Sunday. “His followers include some social workers.” I guess that’s me.

|  | Kīrtanānanda: I think this article will bring a lot of new people.

|  | The Svāmī came down for class. The morning was chilly, and he wore a peach-colored turtleneck jersey his disciples had bought for him at a shop on Orchard Street. They had also started wearing such jerseys – a kind of unofficial uniform. Svāmīji didn’t mention the Times article. He began singing the Sanskrit prayers. Vande ’haṁ śrī-guroḥ: “I offer my obeisances to my spiritual master …” Then he began singing Hare Kṛṣṇa, and the boys joined in. “Sing softly,” Prabhupāda cautioned them.

|  | But no sooner had he spoken than water began pouring down through the cracks in the ceiling. The man upstairs didn’t like early-morning kīrtanas, and he began stomping his feet to show that this flood was no accident.

|  | “What is this?” Prabhupāda looked up, disturbed, but with a touch of amusement. The boys looked around. Water was pouring down in several places. “Get some pots,” he said. A boy ran upstairs to Svāmīji’s apartment to get pots from the kitchen. Soon three pots were catching the water as it dripped in three separate places.

|  | “How does he do it?” asked Umāpati. “Is he pouring water onto the floor?” Prabhupāda asked Brahmānanda to go up and speak to the man, to tell him that the kīrtana would be a quiet one. Then he asked everyone to sit back down amid the dripping and the pots and continue chanting. “Softly,” he said. “Softly.”

|  | That evening, the temple was filled with guests. “It is so much kindness of the Supreme Lord,” Prabhupāda said, “that He wants to associate with you. So you should receive Him. Always chant Hare Kṛṣṇa. Now this language is Sanskrit, and some of you do not know the meaning. Still, it is so attractive that when we chanted Hare Kṛṣṇa in the park, oh, old ladies, gentlemen, boys and girls, all took part. ... But there are also complaints. Just like we are receiving daily reports that our saṅkīrtana movement is disturbing some tenants here.”

|  | Ravīndra-svarūpa was walking down Second Avenue, on his way to the Svāmī’s morning class, when an acquaintance came out of the Gems Spa Candy and News Store and said, “Hey, your Svāmī is in the newspaper. Did you see?” “Yeah,” Ravīndra-svarūpa replied, “The New York Times.”

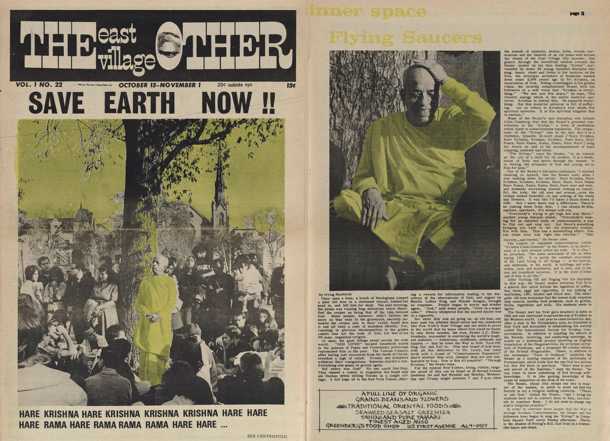

|  | “No,” his friend said. “Today.” And he held up a copy of the latest edition of The East Village Other. The front page was filled with a two-color photo of the Svāmī, his hands folded decorously at his waist, standing in yellow robes in front of the big tree in Tompkins Square Park. He was speaking to a small crowd that had gathered around, and his disciples were at his feet. The big steeple of St. Brigid’s formed a silhouette behind him.

|  | Above the photo was the single headline, “SAVE EARTH NOW!!” and beneath was the mantra: “HARE KRISHNA HARE KRISHNA KRISHNA KRISHNA HARE HARE HARE RAMA HARE RAMA RAMA RAMA HARE HARE.” Below the mantra were the words, “See Centerfold.” That was the whole front page.

|  | Ravīndra-svarūpa took the newspaper and opened to the center, where he found a long article and a large photo of Svāmīji with his left hand on his head, grinning blissfully in an unusual, casual moment. His friend gave him the paper, and Ravīndra-svarūpa hurried to Svāmīji. When he reached the storefront, several boys went along with him to show Svāmīji the paper.

|  | “Look!” Ravīndra-svarūpa handed it over. “This is the biggest local newspaper! Everybody reads it.” Prabhupāda opened his eyes wide. He read aloud, “Save earth now.” And he looked up at the faces of the boys. Umāpati and Hayagrīva wondered aloud what it meant – “Save earth now.” Was it an ecological pun? Was it a reference to staving off nuclear disaster? Was it poking fun at Svāmīji’s evangelism?

|  | “Well,” said Umāpati, “after all, this is The East Village Other. It could mean anything.”

|  | “Svāmīji is saving the earth,” Kīrtanānanda said.

|  | “We are trying to,” Prabhupāda replied, “by Kṛṣṇa’s grace.” Methodically, he put on the eyeglasses he usually reserved for reading the Bhāgavatam and carefully appraised the page from top to bottom. The newspaper looked incongruous in his hands. Then he began turning the pages. He stopped at the centerfold and looked at the picture of himself and laughed, then paused, studying the article. “So,” he said, “read it.” He handed the paper to Hayagrīva.

|  | “Once upon a time...” Hayagrīva began loudly. It was a fanciful story of a group of theologians who had killed an old man in a church and of the subsequent press report that God was now dead. But, the story went on, some people didn’t believe it. They had dug up the body and found it to be “not the body of God, but that of His P.R. man: organized religion. At once the good tidings swept across the wide world. GOD LIVES! ... But where was God?” Hayagrīva read dramatically to an enthralled group...

|  | A full-page ad in The New York Times, offering a reward for information leading to the discovery of the whereabouts of God, and signed by Martin Luther King and Ronald Reagan, brought no response. People began to worry and wonder again. “God,” said some people, “lives in a sugar cube.” Others whispered that the sacred secret was in a cigarette.

|  | But while all this was going on, an old man, one year past his allotted three score and ten, wandered into New York’s East Village and set about to prove to the world that he knew where God could be found. In only three months, the man, Svāmī A. C. Bhaktivedanta, succeeded in convincing the world’s toughest audience – Bohemians, acidheads, potheads, and hippies – that he knew the way to God: Turn Off, Sing Out, and Fall In. This new brand of holy man, with all due deference to Dr. Leary, has come forth with a brand of “Consciousness Expansion” that’s sweeter than acid, cheaper than pot, and nonbustible by fuzz. How is all this possible? “Through Kṛṣṇa,” the Svāmī says.

|  | The boys broke into cheers and applause. Acyutānanda apologized to Svāmīji for the language of the article: “It’s a hippie newspaper.”

|  | “That’s all right,” said Prabhupāda. “He has written it in his own way. But he has said that we are giving God. They are saying that God is dead. But it is false. We are directly presenting, ‘Here is God.’ Who can deny it? So many theologians and people may say there is no God, but the Vaiṣṇava hands God over to you freely, as a commodity: ‘Here is God.’ So he has marked this. It is very good. Save this paper. It is very important.”

|  | The article was long. “For the cynical New Yorker,” it said, “living, visible, tangible proof can be found at 26 Second Avenue, Monday, Wednesday, and Friday between seven and nine.” The article described the evening kīrtanas, quoted from Prabhupāda’s lecture, and mentioned “a rhythmic, hypnotic sixteen-word chant, Hare Kṛṣṇa Hare Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare, sung for hours on end to the accompaniment of hand clapping, cymbals, and bells.” Svāmīji said that simply because the mantra was there, the article was perfect.

|  | The article also included testimony from the Svāmī’s disciples:

|  | I started chanting to myself, like the Svāmī said, when I was walking down the street – Hare Kṛṣṇa Hare Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare – over and over, and suddenly everything started looking so beautiful, the kids, the old men and women … even the creeps looked beautiful … to say nothing of the trees and flowers. It was like I had taken a dozen doses of LSD. But I knew there was a difference. There’s no coming down from this. I can always do this any time, anywhere. It is always with you.

|  | Without sarcasm, the article referred to the Svāmī’s discipline forbidding coffee, tea, meat, eggs, and cigarettes, “to say nothing of marijuana, LSD, alcohol, and illicit sex.” Obviously the author admired Svāmīji: “the energetic old man, a leading exponent of the philosophy of Personalism, which holds that the one God is a person but that His form is spiritual.” The article ended with a hint that Tompkins Square Park would see similar spiritual happenings each weekend: “There in the shadow of Hoving’s Hill, God lives in a trancelike dance and chant.”

|  | October 12

|  | It was to be a “Love-Pageant-Rally,” marking California’s new law prohibiting the possession of LSD. The rally’s promoters urged everyone to come to Tompkins Square Park in elaborate dress. Although the devotees had nothing to do with LSD laws, they took the rally as another opportunity to popularize the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa. So they went, with the Svāmī’s blessings, carrying finger cymbals and a homemade tambourine.

|  | The devotees looked plain in their dark jeans and lightweight zippered jackets. All around them, the dress was extravagant – tie-dyed shirts, tie-bleached jeans, period costumes, painted faces. There was even a circus clown. Tuli Kupferberg of the Fugs rock band carried an American flag with the stars rearranged to spell L-O-V-E. But so far the rally had been a dud – just a strange set of drugged young people milling near the large tree where Svāmīji had chanted and spoken just a few days before.

|  | Svāmīji’s boys made their way through the crowd to a central spot and started chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa. A crowd pressed in close around them. Everyone seemed to be in friendly spirits – just unorganized, without any purpose. The idea behind the rally had been to show love and a pageant of LSD vision, but not much had been happening. Someone was walking around with a bucket of burning incense. Some hippies sat back on the park benches, watching everything through colored glasses. But the kīrtana was attractive, and soon a crowd gathered around the boys as they chanted.

|  | Kīrtanānanda, his shaved head covered with a knit skullcap, stood beside tall Jagannātha, who, with his dark-framed glasses and wavy hair, looked like a great horned owl playing hand cymbals. Umāpati, also playing hand cymbals, looked thoughtful. Brahmānanda sat on the ground in front of them, his eyes closed and his mouth widely open, chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa. Beside him and looking moody sat Raphael, and next to him, ascetically thin-faced Ravīndra-svarūpa. Close by, a policeman stood watching.

|  | The hippies began to pick up the chanting. They had come together, but there had been no center, no lecture, no amplified music. But now they began clapping and swaying, getting into the chanting as if it were their single purpose. The chanting grew stronger, and after an hour the group broke into a spontaneous dance. Joining hands and singing out, “Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare,” they skipped and danced together, circling the tree and Svāmīji’s disciples. To the hippies, it was in fact a Love-Pageant-Rally, and they had found the love and peace they were searching for – it was in this mantra. Hare Kṛṣṇa had become their anthem, their reason for coming together, the life of the Love-Pageant-Rally. They didn’t know exactly what the mantra was, but they accepted it as something deep within the soul, a metaphysical vibration – they tuned in to it. Even the clown began chanting and dancing. Only the policeman remained aloof and sober, though he also could see that the new demonstration would be a peaceful one. The dance continued, and only the impending dusk brought the Love-Pageant-Rally to a close.

|  | The devotees hurried back to Svāmīji to tell him all that had happened. He had been sitting at his desk, translating the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. Although he had not been physically present at the kīrtana, his disciples had acted on his instruction. So even without leaving his room, he was spreading the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa. Now he sat waiting for the report.

|  | They burst into his room with shining eyes, flushed faces, and hoarse voices, relating the good news. Not only had they dutifully chanted, but hundreds of people had joined them and sung and danced in a big circle, in a spirit of unity. “Svāmīji, you should have seen,” Brahmānanda exclaimed, his voice now exhausted from chanting. “It was fantastic, fantastic!” Prabhupāda looked from one face to another, and he also became like them, elated and hopeful that the chanting could go on like this. They had proved that their chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa could lead the love and peace movement. It could grow, and hundreds could take part. “It is up to you to spread this chanting,” Svāmīji told them. “I am an old man, but you are young, and you can do it.”

|  | October 13

|  | The Village Voice ran four large photographs of the Love-Pageant- Rally. The article stated:

|  | The backbone of the celebration was the mantras, holy chants from the Sanskrit Bhagavad Gita, and for three hours it became like a boat on a sea of rhythmic chanting. Led by fifteen disciples of Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, who operates from a storefront on Second Avenue, the mantras ebbed and flowed with the rhythm of drums, flutes, and soda-cap tambourines.

|  | October 18

|  | It was Sunday. And again they went to Tompkins Square Park. Svāmīji played the bongo as before, striking the drumhead deftly as ever, his nimble fingers creating drum rolls, as he sat on the rug in the autumn afternoon. His authentic, melodic voice recited the prayers to the previous spiritual masters: Bhaktivinoda, Gaurakiśora, Bhaktisiddhānta – the centuries-old disciplic succession of which he was the living representative, now in the 1960s, in this remote part of the world. He sang their names in duty, deference, and love, as their servant. He sat surrounded by his American followers under the tall oak tree amid the mazelike fences of the park.